Vue lecture

SpaceX acquires xAI in bid to develop orbital data centers

SpaceX has acquired xAI, an artificial intelligence company also run by Elon Musk, as part of his effort to develop orbital data centers.

The post SpaceX acquires xAI in bid to develop orbital data centers appeared first on SpaceNews.

At Blue Origin, Hegseth escalates criticism of legacy defense procurement

Pentagon chief sharpens warnings to defense contractors over delivery, pay and buybacks

The post At Blue Origin, Hegseth escalates criticism of legacy defense procurement appeared first on SpaceNews.

Unusually Small Dinosaur Fossil Helps Fill a 70-Million-Year Gap in Ornithopod Evolution

A Small Genetic Shift May Have Launched Vertebrate Evolution

Planets With Two Suns Are Almost Impossible To Find — General Relativity May Be Why

HHS Is Using AI Tools From Palantir to Target ‘DEI’ and ‘Gender Ideology’ in Grants

UK Space Agency CEO stepping down as agency folds into government

Paul Bate is stepping down as CEO of the UK Space Agency at the end of March as it transitions from a standalone body into the British government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

The post UK Space Agency CEO stepping down as agency folds into government appeared first on SpaceNews.

European Wildcats Are Slowly Making a Comeback in the Forests of Central Europe

Lawmakers spend big on home state science projects

What is the Nipah Virus and Should We Be Concerned?

From Cucumber Salad to Dubai Chocolate — How TikTok Shapes Food Choices

House NASA bill seeks details on lunar lander and spacesuit development

A NASA authorization bill the House Science Committee is scheduled to take up this week would require closer scrutiny of lunar lander and spacesuit development for the Artemis program.

The post House NASA bill seeks details on lunar lander and spacesuit development appeared first on SpaceNews.

Amazon buys 10 more Falcon 9 launches

Amazon has purchased an additional 10 Falcon 9 launches from SpaceX as part of its efforts to accelerate deployment of its broadband satellite constellation.

The post Amazon buys 10 more Falcon 9 launches appeared first on SpaceNews.

Alzheimer’s-Related Memory Concerns Linked to Glitches in the Brain’s Replay Process

New project takes aim at theory-experiment gap in materials data

Condensed-matter physics and materials science have a silo problem. Although researchers in these fields have access to vast amounts of data – from experimental records of crystal structures and conditions for synthesizing specific materials to theoretical calculations of electron band structures and topological properties – these datasets are often fragmented. Integrating experimental and theoretical data is a particularly significant challenge.

Researchers at the Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics and the Institute of Physics (IOP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently decided to address this challenge. Their new platform, MaterialsGalaxy, unifies data from experiment, computation and scientific literature, making it easier for scientists to identify previously hidden relationships between a material’s structure and its properties. In the longer term, their goal is to establish a “closed loop” in which experimental results validate theory and theoretical calculations guide experiments, accelerating the discovery of new materials by leveraging modern artificial intelligence (AI) techniques.

Physics World spoke to team co-leader Quansheng Wu to learn more about this new tool and how it can benefit the materials research community.

How does MaterialsGalaxy work?

The platform works by taking the atomic structure of materials and mathematically mapping it into a vast, multidimensional vector space. To do this, every material – regardless of whether its structure is known from experiment, from a theoretical calculation or from simulation – must first be converted into a unique structural vector that acts like a “fingerprint” for the material.

Then, when a MaterialsGalaxy user focuses on a material, the system automatically identifies its nearest neighbors in this vector space. This allows users to align heterogeneous data – for example, linking a synthesized crystal in one database with its calculated topological properties in another – even when different data sources define the material slightly differently.

The vector-based approach also enables the system to recommend “nearest neighbour” materials (analogs) to fill knowledge gaps, effectively guiding researchers from known data into unexplored territories. It does this by performing real-time vector similarity searches to dynamically link relevant experimental records, theoretical calculations and literature information. The result is a comprehensive profile for the material.

Where does data for MaterialsGalaxy come from?

We aggregated data from three primary channels: public databases; our institute’s own high-quality internal experimental records (known as the MatElab platform); and the scientific literature. All data underwent rigorous standardization using tools such as the pymatgen (Python Materials Genomics) materials analysis code and the spglib crystal structure library to ensure consistent definitions for crystal structures and physical properties.

Who were your collaborators on this project?

This project is a multi-disciplinary effort involving a close-knit collaboration among several research groups at the IOP, CAS and other leading institutions. My colleague Hongming Weng and I supervised the core development and design under the strategic guidance of Zhong Fang, while Tiannian Zhu (the lead author of our Chinese Physics B paper about MaterialsGalaxy) led the development of the platform’s architecture and core algorithms, as well as its technical implementation.

We enhanced the platform’s capabilities by integrating several previously published AI-driven tools developed by other team members. For example, Caiyuan Ye contributed the Con-CDVAE model for advanced crystal structure generation, while Jiaxuan Liu contributed VASPilot, which automates and streamlines first-principles calculations. Meanwhile, Qi Li contributed PXRDGen, a tool for simulating and generating powder X-ray diffraction patterns.

Finally, much of the richness of MaterialsGalaxy stems from the high-quality data it contains. This came from numerous collaborators, including Weng (who contributed the comprehensive topological materials database, Materiae), Youguo Shi (single-crystal growth), Shifeng Jin (crystal structure and diffraction), Jinbo Pan (layered materials), Qingbo Yan (2D ferroelectric materials), Yong Xu (nonlinear optical materials), and Xingqiu Chen (topological phonons). My own contribution was a library of AI-generated crystal structures produced by the Con-CDVAE model.

What does MaterialsGalaxy enable scientists to do that they couldn’t do before?

One major benefit is that it prevents researchers from becoming stalled when data for a specific material is missing. By leveraging the tool’s “structural analogs” feature, they can look to the properties or growth paths of similar materials for insights – a capability not available in traditional, isolated databases.

We also hope that MaterialsGalaxy will offer a bridge between theory and experiment. Traditionally, experimentalists tend to consult the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database while theorists check the Materials Project. Now, they can view the entire lifecycle of a material – from how to grow a single crystal (experiment) to its topological invariants (theory) – on a single platform.

Beyond querying known materials, MaterialsGalaxy also allows researchers to use integrated generative AI models to create new structures. These can be immediately compared against the known database to assess synthesis feasibility and potential performance throughout the “vertical comparison” workflow.

What do you plan to do next?

We’re focusing on enhancing the depth and breadth of the tool’s data fusion. For example, we plan to develop representations based on graph neural networks (GNNs) to better handle experimental data that may contain defects or disorder, thereby improving matching accuracy.

We’re also interested in moving beyond crystal structure by introducing multi-modal anchors such as electronic band structures, X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns and spectroscopic data. To do this, we plan to utilize technologies derived from computational linguistics and information processing (CLIP) to enable cross-modal retrieval, for example searching for theoretical band data by uploading an experimental XRD pattern.

Separately, we want to continue to expand our experimental data coverage, specifically targeting synthesis recipes and “failed” experimental records, which are crucial for training the next generation of “AI-enabled” scientists. Ultimately, we plan to connect an even wider array of databases, establishing robust links between them to realize a true Materials Galaxy of interconnected knowledge.

The post New project takes aim at theory-experiment gap in materials data appeared first on Physics World.

The pros and cons of patenting

For any company or business, it’s important to recognize and protect intellectual property (IP). In the case of novel inventions, which can include machines, processes and even medicines, a patent offers IP protection and lets firms control how those inventions are used. Patents, which in most countries can be granted for up to 20 years, give the owner exclusive rights so that others can’t directly copy the creation. A patent essentially prevents others from making, using or selling your invention.

But there are more reasons for holding a patent than IP protection alone. In particular, patents go some way to protecting the investment that may have been necessary to generate the IP in the first place, such as the cost of R&D facilities, materials, labour and expertise. Those factors need to be considered when you’re deciding if patenting is the right approach or not.

Patents are tangible assets that can be sold to other businesses or licensed for royalties to provide your compay with regular income

Patents are in effect a form of currency. Counting as tangible assets that add to the overall value of a company, they can be sold to other businesses or licensed for royalties to provide regular income. Some companies, in fact, build up or acquire significant patent portfolios, which can be used for bargaining with competitors, potentially leading to cross-licensing agreements where both parties agree to use each other’s technology.

Patents also say something about the competitive edge of a company, by demonstrating technical expertise and market position through the control of a specific technology. Essentially, patents give credibility to a company’s claims of its technical know-how: a patent shows investors that a firm has a unique, protected asset, making the business more appealing and attractive to further investment.

However, it’s not all one-way traffic and there are obligations on the part of the patentee. Firstly, a patent holder has to reveal to the world exactly how their invention works. Governments favour this kind of public disclosure as it encourages broader participation in innovation. The downside is that whilst your competitors cannot directly copy you, they can enhance and improve upon your invention, provided those changes aren’t covered by the original patent.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that a patent holder is responsible for patent enforcement and any ensuing litigation; a patent office will not do this for you. So you’ll have to monitor what your competitors are up to and decide on what course of action to take if you suspect your patent’s been infringed. Trouble is, it can sometimes be hard to prove or disprove an infringement – and getting the lawyers in can be expensive, even if you win.

Money talks

Probably the biggest consideration of all is the cost and time involved in making a patent application. Filing a patent requires a rigorous understanding of “prior art” – the existing body of relevant knowledge on which novelty is judged. You’ll therefore need to do a lot of work finding out about relevant established patents, any published research and journal articles, along with products or processes publicly disclosed before the patent’s filing date.

Before it can be filed with a patent office, a patent needs to be written as a legal description, which includes all the legwork like an abstract, background, detailed specifications, drawings and claims of the invention. Once filed, an expert in the relevant technical field will be assigned to assess the worth of the claim; this examiner must be satisfied that the application is both unique and “non-obvious” before it’s granted.

Even when the invention is judged to be technically novel, in order to be non-obvious, it must also involve an “inventive step” that would not be obvious to a person with “ordinary skill” in that technical field at the time of filing. The assessment phase can result in significant to-ing and fro-ing between the examiner and the applicant to determine exactly what is patentable. If insufficient evidence is found, the patent application will be refused.

Patents are only ever granted in a particular country or region, such as Europe, and the application process has to be repeated for each new place (although the information required is usually pretty similar). Translations may be required for some countries, there are fees for each application and, even if a patent is granted, you have to pay an additional annual bill to maintain the patent (which in the UK rises year on year).

Patents can take years to process, which is why many companies pay specialized firms to support their applications

Patent applications, in other words, can be expensive and can take years to process. That’s why many companies pay specialized firms to support their patent applications. Those firms employ patent attorneys – legal experts with a technical background who help inventors and companies manage their IP rights by drafting patent applications, navigating patent office procedures and advising on IP strategy. Attorneys can also represent their clients in disputes or licensing deals, thereby acting as a crucial bridge between science/engineering and law.

Perspiration and aspiration

It’s impossible to write about patents without mentioning the impact that Thomas Edison had as an inventor. During the 20th century, he became the world’s most prolific inventor with a staggering 1093 US patents granted in his lifetime. This monumental achievement remained unsurpassed until 2003, when it was overtaken by the Japanese inventor Shunpei Yamazaki and, more recently, by the Australian “patent titan” Kia Silverbrook in 2008.

Edison clearly saw there was a lot of value in patents, but how did he achieve so much? His approach was grounded in systematic problem solving, which he accomplished through his Menlo Park lab in New Jersey. Dedicated to technological development and invention, it was effectively the world’s first corporate R&D lab. And whilst Edison’s name appeared on all the patents, they were often primarily the work of his staff; he was effectively being credited for inventions made by his employees.

I have a love–hate relationship with patents or at least the process of obtaining them

I will be honest; I have a love–hate relationship with patents or at least the process of obtaining them. As a scientist or engineer, it’s easy to think all the hard work is getting an invention over the line, slogging your guts out in the lab. But applying for a patent can be just as expensive and time-consuming, which is why you need to be clear on what and when to patent. Even Edison grew tired of being hailed a genius, stating that his success was “1% inspiration and 99% perspiration”.

Still, without the sweat of patents, your success might be all but 99% aspiration.

The post The pros and cons of patenting appeared first on Physics World.

CesiumAstro to scale operations with $470 million in equity and debt financing

SAN FRANCISCO – CesiumAstro is preparing for rapid expansion thanks to an influx of cash announced Feb. 2: $270 million in equity and $200 million in debt financing. CesiumAstro raised […]

The post CesiumAstro to scale operations with $470 million in equity and debt financing appeared first on SpaceNews.

Starlink and the unravelling of digital sovereignty

In January 2026, Iranian authorities shut down landline and mobile telecommunications infrastructure in the country to clamp down on coordinated protests. Starlink terminals, which were discreetly mounted on rooftops, helped Iranian protesters bypass this internet blackout. The role played by Starlink in the recent Iranian protests challenges the notion of digital sovereignty and promotes corporate […]

The post Starlink and the unravelling of digital sovereignty appeared first on SpaceNews.

Transcelestial to provide satellite laser communication terminals to Gilmour Space

Transcelestial, a startup developing optical communications technologies, has signed an agreement with Gilmour Space Technologies to incorporate its technology on Gilmour Space spacecraft.

The post Transcelestial to provide satellite laser communication terminals to Gilmour Space appeared first on SpaceNews.

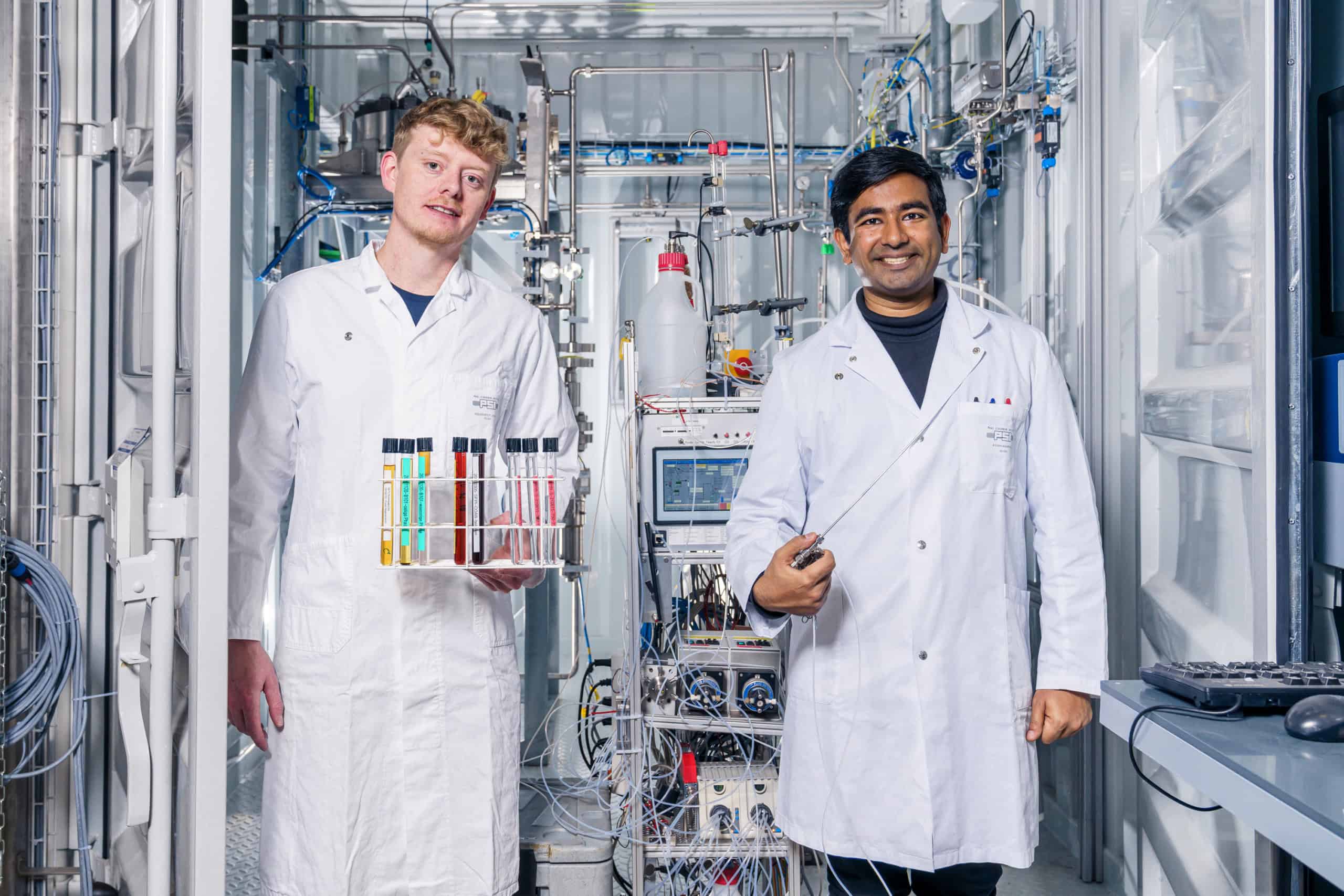

Practical impurity analysis for biogas producers

Biogas is a renewable energy source formed when bacteria break down organic materials such as food waste, plant matter, and landfill waste in an oxygen‑free (anaerobic) process. It contains methane and carbon dioxide, along with trace amounts of impurities. Because of its high methane content, biogas can be used to generate electricity and heat, or to power vehicles. It can also be upgraded to almost pure methane, known as biomethane, which can directly replace natural fossil gas.

Strict rules apply to the amount of impurities allowed in biogas and biomethane, as these contaminants can damage engines, turbines, and catalysts during upgrading or combustion. EN 16723 is the European standard that sets maximum allowable levels of siloxanes and sulfur‑containing compounds for biomethane injected into the natural gas grid or used as vehicle fuel. These limits are extremely low, meaning highly sensitive analytical techniques are required. However, most biogas plants do not have the advanced equipment needed to measure these impurities accurately.

The researchers developed a new, simpler method to sample and analyse biogas using GC‑ICP‑MS. Gas chromatography (GC) separates chemical compounds in a gas mixture based on how quickly they travel through a column. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP‑MS) then detects the elements within those compounds at very low concentrations. Crucially, this combined method can measure both siloxanes and sulfur compounds simultaneously. It avoids matrix effects that can limit other detectors and cause biased or ambiguous results. It also achieves the very low detection limits required by EN 16723.

The sampling approach and centralized measurement enables biogas plants to meet regulatory standards using an efficient, less complex, and more cost‑effective method with fewer errors. Overall, this research provides a practical, high‑accuracy tool that makes reliable biogas impurity monitoring accessible to plants of all sizes, strengthening biomethane quality, protecting infrastructure, and accelerating the transition to cleaner energy systems.

Read the full article

Ayush Agarwal et al 2026 Prog. Energy 8 015001

Do you want to learn more about this topic?

Household biogas technology in the cold climate of low-income countries: a review of sustainable technologies for accelerating biogas generation Sunil Prasad Lohani et al. (2024)

The post Practical impurity analysis for biogas producers appeared first on Physics World.

Saudi Space Agency Announces Winners of Global ‘DebriSolver’ Competition at Space Debris Conference

The Saudi Space Agency announced on Tuesday the names of the winning teams of the global “DebriSolver” competition, one of the flagship initiatives accompanying the Space Debris Conference 2026. Launched […]

The post Saudi Space Agency Announces Winners of Global ‘DebriSolver’ Competition at Space Debris Conference appeared first on SpaceNews.

With attention on orbital data centers, the focus turns to economics

One of the biggest questions in the tech sector has been if AI is the future, where does all the infrastructure go? Some space industry leaders — including Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos — believe the answer could be in orbit, via space-based data centers. That idea has gained attention in recent weeks. Musk is […]

The post With attention on orbital data centers, the focus turns to economics appeared first on SpaceNews.

How to Use Physics to Escape an Ice Bowl