Vue lecture

Lawsuit aims to overturn many NIH grant terminations

Uncovering a Mysterious Amphibian Mass Die-Off from 230 Million Years Ago

Starquakes Serenade Us With Songs of the Galaxy’s Formation

Metal Contaminants From Mines Lurk in Rocky Mountain Snow

A Tiny, Rice-Sized Pacemaker Can Biodegrade in Time, Helping Newborns

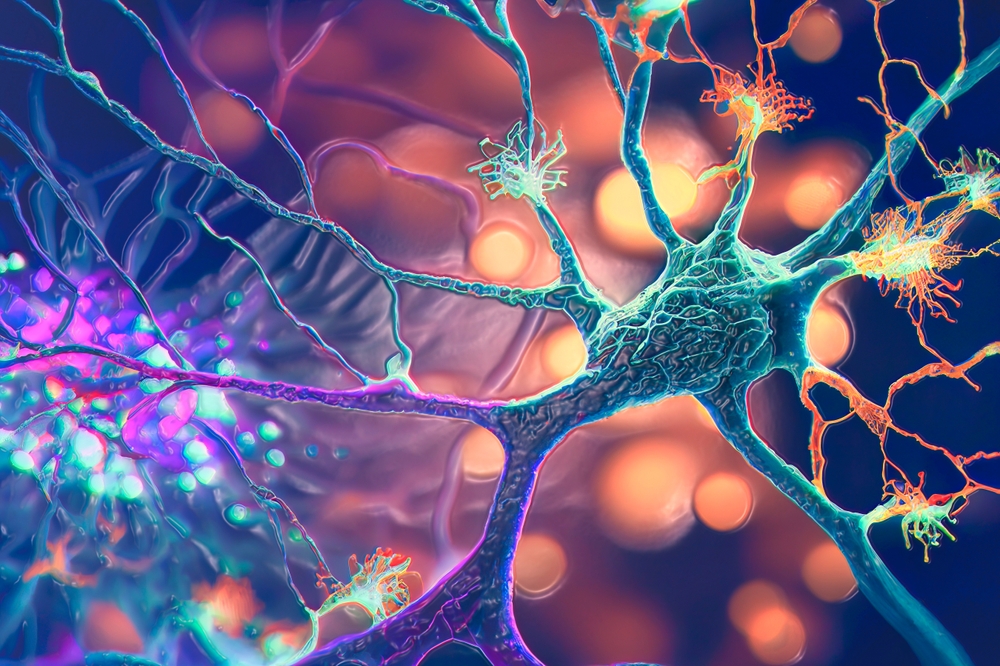

Why the Brain Keeps Track of Those Painful Food Poisoning Memories

Neanderthals Continued to Grow into Adulthood — Even Their Faces

Washington Harbour Partners invests in startup Turion Space

The investment, which marks Washington Harbour’s first in Turion Space, was part of a broader funding round

The post Washington Harbour Partners invests in startup Turion Space appeared first on SpaceNews.

Project Kuiper readies long-awaited operational satellite launch

ULA is set to loft the first 27 satellites of the more than 3,200 planned for Amazon’s Project Kuiper broadband constellation April 9, roughly a year behind schedule as the company races to meet deployment deadlines.

The post Project Kuiper readies long-awaited operational satellite launch appeared first on SpaceNews.

Skeletons from ‘green Sahara’ offer genetic peek at a lost human population

Unusual dinosaur tracks in Scotland reveal an ancient watering hole

Frontgrade Gaisler Launches New GRAIN Line and Wins SNSA Contract to Commercialize First Energy-Efficient Neuromorphic AI for Space Applications

Gothenburg, Sweden (April 2, 2025) – The Swedish National Space Agency (SNSA) has awarded Frontgrade Gaisler, a leading provider of radiation-hardened microprocessors for space missions, a contract to commercialize the […]

The post Frontgrade Gaisler Launches New GRAIN Line and Wins SNSA Contract to Commercialize First Energy-Efficient Neuromorphic AI for Space Applications appeared first on SpaceNews.

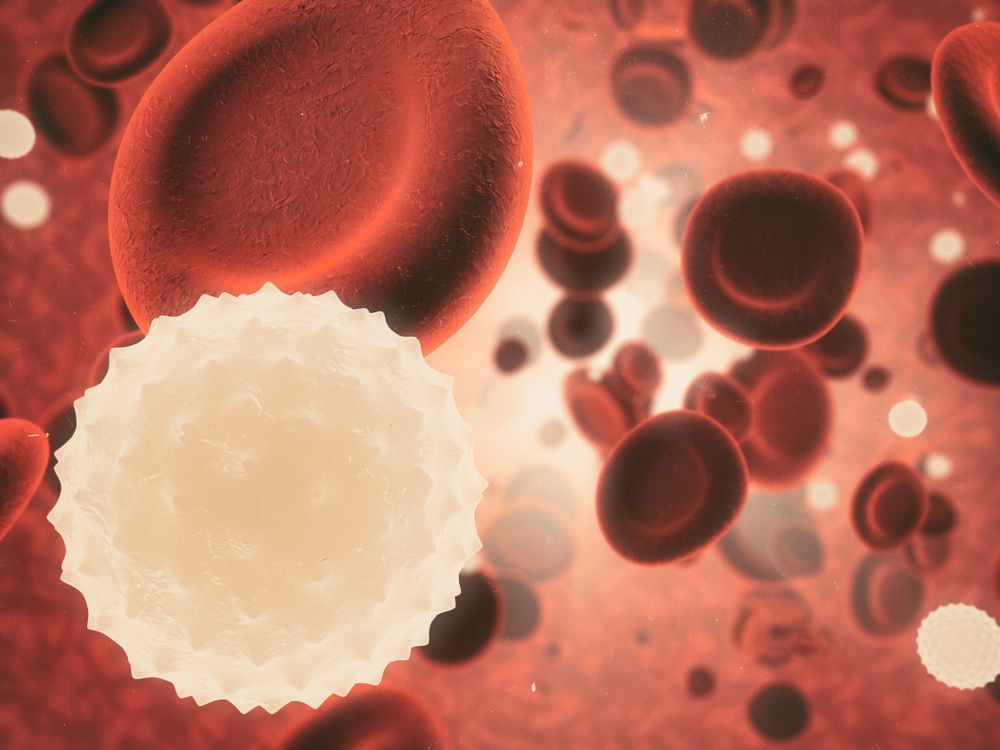

Zwitterions make medical implants safer for patients

A new technique could reduce the risk of blood clots associated with medical implants, making them safer for patients. The technique, which was developed by researchers at the University of Sydney, Australia, involves coating the implants with highly hydrophilic molecules known as zwitterions, thereby inhibiting the build-up of clot-triggering proteins.

Proteins in blood can stick to the surfaces of medical implants such as heart valves and vascular stents. When this happens, it produces a cascade effect in which multiple mechanisms lead to the formation of extensive clots and fibrous networks. These clots and networks can impair the function of implanted medical devices so much that invasive surgery may be required to remove or replace the implant.

To prevent this from happening, the surfaces of implants are often treated with polymeric coatings that resist biofouling. Hydrophilic polymeric coatings such as polyethylene glycol are especially useful, as their water-loving nature allows a thin layer of water to form between them and the surface of the implants, held in place via hydrogen and/or electrostatic bonds. This water layer forms a barrier that prevents proteins from sticking, or adsorbing, to the implant.

An extra layer of zwitterions

Recently, researchers discovered that polymers coated with an extra layer of small molecules called zwitterions provided even more protection against protein adsorption. “Zwitter” means “hybrid” in German; hence, zwitterions are molecules that carry both positive and negative charge, making them neutrally charged overall. These molecules are also very hydrophilic and easily form tight bonds with water molecules. The resulting layer of water has a structure that is similar to that of bulk water, which is energetically stable.

A further attraction of zwitterionic coatings for medical implants is that zwitterions are naturally present in our bodies. In fact, they make up the hydrophilic phospholipid heads of mammalian cell membranes, which play a vital role in regulating interactions between biological cells and the extracellular environment.

Plasma functionalization

In the new work, researchers led by Sina Naficy grafted nanometre-thick zwitterionic coatings onto the surfaces of implant materials using a technique called plasma functionalization. They found that the resulting structures reduce the amount of fibrinogen proteins that adsorb onto the implants by roughly nine-fold and decrease blood clot formation (thrombosis) by almost 75%.

Naficy and colleagues achieved their results by optimizing the density, coverage and thickness of the coating. This was critical for realizing the full potential of these materials, they say, because a coating that is not fully optimized would not reduce clotting.

Naficy tells Physics World that the team’s main goal is to enhance the surface properties of medical devices. “These devices when implanted are in contact with blood and can readily cause thrombosis or infection if the surface initiates certain biological cascade reactions,” he explains. “Most such reactions begin when specific proteins adsorb on the surface and activate the next stage of cascade. Optimizing surface properties with the aid of zwitterions can control / inhibit protein adsorption, hence reducing the severity of adverse body reactions.”

The researchers say they will now be evaluating the long-term stability of the zwitterion-polymer coatings and trying to scale up their grafting process. They report their work in Communications Materials and Cell Biomaterials.

The post Zwitterions make medical implants safer for patients appeared first on Physics World.

Biotech is the launchpad for human survival in space

With NASA’s Artemis program preparing for the first crewed moon landing since 1972, four commercial space stations in development, and companies like SpaceX setting their sights on Mars, long-duration human […]

The post Biotech is the launchpad for human survival in space appeared first on SpaceNews.

Slingshot adapting satellite ‘fingerprinting’ technology for military applications

The company was awarded an SBIR Phase 3 contract to further develop satellite "fingerprinting" technology

The post Slingshot adapting satellite ‘fingerprinting’ technology for military applications appeared first on SpaceNews.

Linking Inflammation to Depression Could Yield More Targeted Treatment

CERN releases plans for the ‘most extraordinary instrument ever built’

The CERN particle-physics lab near Geneva has released plans for the 15bn SwFr (£13bn) Future Circular Collider (FCC) – a huge 91 km circumference machine. The three-volume feasibility study, released on 31 March, calls for the giant accelerator to collide electrons with positrons to study the Higgs boson in unprecedented detail. If built, the FCC would replace the 27 km Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which will come to an end in the early 2040s.

Work on the FCC feasibility study began in 2020 and the report examines the physics objectives, geology, civil engineering, technical infrastructure and territorial and environmental impact. It also looks at the R&D needed for the accelerators and detectors as well as the socioeconomic benefits and cost.

The study, involving some 150 institutes in over 30 countries, took into account some 100 different scenarios for the collider before landing on a ring circumference of 90.7 km that would be built underground at a depth of about 200 m, on average.

The FCC would also contain eight surface sites to access the tunnel with seven in France and one in Switzerland, and four main detectors. “The design is such that there is minimal impact on the surface, but with the best possible physics output,” says FCC study leader Michael Benedikt.

The funding model for the FCC is still a work in progress, but it is estimated that at least two-thirds of the cost of building the FCC-ee will come from CERN’s 24 member states.

Four committees will now review the feasibility study, beginning with CERN’s scientific committee in July. It will then go to a cost-review panel before being reviewed by the CERN council’s scientific and finance committees. In November, the CERN council will then examine the proposal with a decision to go ahead taken in 2028.

If given the green light, construction on the FCC electron-positron machine, dubbed FCC-ee, would begin in 2030 and it would start operations in 2047, a few years after the High Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) closes down, and run for about 15 years. It’s main aim would be to study the Higgs boson with a much better precision that the LHC.

The FCC feasibility study then calls for a hadron machine, dubbed FCC-hh, to replace the FCC-ee in the existing 91 km tunnel. It would be a “discovery machine”, smashing together protons at high energy with the aim of creating new particles. If built, the FCC-hh will begin operation in 2073 and run to the end of the century.

The original design energy for the FCC-hh was to reach 100 TeV but that has now been reduced to 85 TeV. That is mostly due to the uncertainty in magnet technology. The HL-LHC will use 12 T superconducting quadrupole magnets made from niobium-tin (Nb3Sn) to squeeze the beams to boost the luminosity.

CERN engineers think it is possible to increase that to 14 T and if this was used for the FCC it would result in a collision centre-of-mass energy of about 85 TeV. “It’s a prudent approach at this stage,” noted Fabiola Gianotti, current CERN director-general, adding that the FCC would be “the most extraordinary instrument ever built.”

The original design called for high-temperature superconducting magnets, such as so-called ReBCO tapes, and CERN is looking into such technology. If it came to fruition in the necessary timescales and was implemented in the FCC-hh then it could push the energy to 120 TeV.

China plans

One potential spanner in the works is China’s plans for a very similar machine called the Circular Election-Positron Collider (CEPC). A decision on the CEPC could come this year with construction beginning in 2027.

Yet officials at CERN are not concerned. They point to the fact that many different colliders have been built by CERN, which has the expertise as well as infrastructure to build such a huge collider. “Even if China goes ahead, I hope the decision is to compete,” says CERN council president Costas Fountas. “Just like Europe did with the LHC when the US started to build the [cancelled] Superconducting Super Collider.”

If the CERN council decides, however, not to go ahead with the FCC, then Gianotti says that other designs to replace the LHC are still on the table such as a linear machine or a demonstrator muon collider.

The post CERN releases plans for the ‘most extraordinary instrument ever built’ appeared first on Physics World.

This Startup Says It Can Clean Your Blood of Microplastics

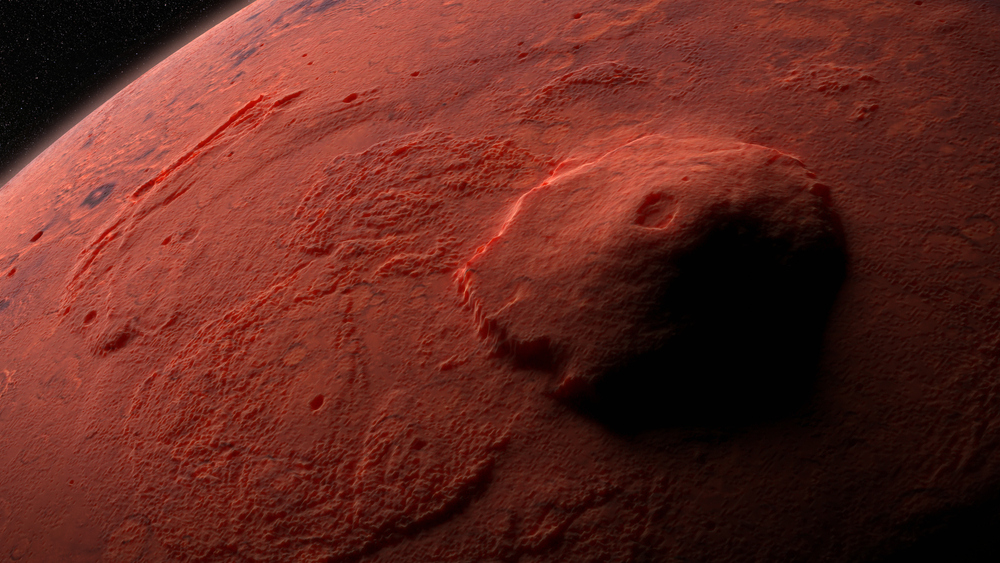

JAXA institute studying Mars lander concept

WASHINGTON — An institute in Japan’s space agency is pursuing a concept that could allow the agency to send small rovers to the surface of Mars. In a talk at […]

The post JAXA institute studying Mars lander concept appeared first on SpaceNews.

CLPS companies seek expanded opportunities for commercial lunar landers

Lunar lander companies want NASA to revise and expand its approach to buy services as Congress raises questions about NASA’s handling of VIPER.

The post CLPS companies seek expanded opportunities for commercial lunar landers appeared first on SpaceNews.

So you think you know Roger Penrose? Be prepared to be shocked

I was unprepared for the Roger Penrose that I met in The Impossible Man. As a PhD student training in relativity and quantum gravity at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada, I once got to sit next to Penrose. Unsure of what to say to the man whose ideas about black-hole singularities are arguably why I took an interest in becoming a physicist, I asked him how he had come up with the idea for the space-time diagrams now known as “Penrose diagrams”.

Penrose explained to me that he simply couldn’t make sense of space-time without them, that was all. He spoke in kind terms, something I wasn’t quite used to. I was more familiar with people reacting as if my questions were stupid or impertinent. What I felt from Penrose – who eventually shared the 2020 Nobel Prize for Physics with Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for his work on singularities – was humility and generosity.

The Penrose of The Impossible Man isn’t so much humble as oblivious and, in my reading, quite spoiled

In hindsight, I wonder if I overread him, or if, having been around too many brusque theoretical physicists, my bar as a PhD student was simply too low. The Penrose of The Impossible Man isn’t so much humble as oblivious and, in my reading, quite spoiled. As a teenager he was especially good at taking care of his sister and her friends, generous with his time and thoughtfulness. But it ends there.

As we learn in this biography – written by the Canadian journalist Patchen Barss – one of those young friends, Judith Daniels, later became the object of Penrose’s affection when he was a distinguished faculty member at the University of Oxford in his 40s. A significant fraction of the book is centred on Penrose’s relationship with Daniels, whom he became reacquainted with in the early 1970s when she was an undergraduate studying mathematics at John Cass College in London.

At the time Penrose was unhappily married to Joan, an American he’d met in 1958 when he was a postdoc at the University of Cambridge. In Barss’s telling, Penrose essentially forces Daniels into the position of muse. He writes her copious letters explaining his intellectual ideas and communicating his inability to get his work done without replies from her, which he expects to contain critical analyses of his scientific proposals.

The letters are numerous and obsessive, even when her replies are thin and distant. Eventually, Penrose also begins to request something more – affection and even love. He wants a relationship with her. Barss never exactly states that this was against Daniels’s will, but he offers readers sufficient details of her letters to Penrose that it’s hard to draw another conclusion.

Unanswered questions

Barss was able to read her letters because they had been returned to Penrose after Daniels’s death in 2005. Penrose, however, never re-examined any of them until Barss interviewed him for this biography. This raises a lot of questions that remain unanswered by the end of the book. In particular, why did Daniels continue to participate in a correspondence that was eventually thousands of pages long on Penrose’s side?

Judith Daniels was a significant figure in Penrose’s life, yet her death and memory seem to have been unremarkable to him for much of his later life

My theory is that Daniels felt she owed it to this great man of science. She also confesses at one point that she had a childhood crush on him. Her affection was real, even if not romantic; it is as if she was trapped in the dynamic. Penrose’s lack of curiosity about the letters after her death is also strange to me. Daniels was a significant figure in his life, yet her death and memory seem to have been unremarkable to him for much of his later life.

By the mid-1970s, when Daniels was finally able to separate herself from what was – on Penrose’s side – an extramarital emotional affair, Penrose went seeking new muses. They were always female students of mathematics and physics.

Just when it seems like we’ve met the worst of Penrose’s treatment of women, we’re told about his “physical aggression” toward his eventual ex-wife Joan and his partial abandonment of the three sons they had together. This is glossed over very quickly. And it turns out there is even more.

Penrose, like many of his contemporaries, primarily trained male students. Eventually he did take on one woman, Vanessa Thomas, who was a PhD student in his group at Oxford’s Mathematical Institute, where he’d moved in 1972.

Thomas never finished her PhD; Penrose pursued her romantically and that was the end of her doctorate. As scandalous as this is, I didn’t find the fact of the romance especially shocking because it is common enough in physics, even if it is increasingly frowned upon and, in my opinion, generally inappropriate. For better or worse, I can think of other examples of men in physics who fell in love with women advisees.

But in all the cases I know of, the woman has gone on to complete her degree either under his or someone else’s supervision. In these same cases, the age difference was usually about a decade. What happened with Thomas – who married Penrose in 1988 – seems like the worst-case scenario: a 40-year age difference and a budding star of mathematics, reduced to serving her husband’s career. Professional boundaries were not just transgressed, but obliterated.

Barss chooses not to offer much in the way of judgement about the impact that Penrose had on the women in science whom he made into muses and objects of romantic affection. The only exception is Ivette Fuentes, who was already a star theoretical physicist in her own right when Penrose first met her in 2012. Interview snippets with Fuentes reveal that the one time Penrose spoke of her as a muse, she rejected him and their friendship until he apologized.

No woman, it seems, had ever been able to hold him to the fire before. Fuentes does, however, describe how Penrose gave her an intellectual companion, something she’d previously been denied by the way the physics community is structured around insider “families” and pedigrees. It is interesting to read this in the context of Penrose’s own upbringing as landed gentry.

Gilded childhood

An intellectually precocious child growing up in 1930s England, Penrose is handed every resource for his intellectual potential to blossom. When he notices a specific pattern linking addition and multiplication, an older sibling is on hand to show him there’s a general rule from number theory that explains the pattern. The family at this point, we’re told, has a cook and a maid who doubles as a nanny. Even in a community of people from well-resourced backgrounds, Penrose stands out as an especially privileged example.

When the Second World War starts, his family readily secures safe passage to a comfortable home in Canada – a privilege related to their status as welcomed members of Britain’s upper class and one that was not afforded to many continental European Jewish families at the time (Penrose’s mother and therefore Penrose was Jewish by descent). Indeed, Canada admitted the fewest Jewish refugees of any Allied nation and famously denied entry to the St Louis, which was sent back to Europe, where a third of its 937 Jewish passengers were murdered in the Holocaust.

In Ontario, the Penrose children have a relatively idyllic experience. Throughout the rest of his childhood and his adult life, the path has been continuously smoothed for Penrose, either by his parents (who bought him multiple homes) or mentors and colleagues who believed in his genius. One is left wondering how many other people might have such a distinguished career if, from birth, they are handed everything on a silver platter and never required to take responsibility for anything.

To tell these and later stories, Barss relies heavily on interviews with Penrose. Access to their subject for any biographer is tricky. While it creates a real opportunity for the author, there is also the challenge of having a relationship with someone whose memories you need to question. Barss doesn’t really interrogate Penrose’s memory but seems to take them as gospel.

During the first half of the book, I wondered repeatedly if The Impossible Man is effectively a memoir told in the third person. Eventually, Barss does allow other voices to tell the story. Ultimately, though, this is firmly a book told from Penrose’s point of view. Even the inclusion of Daniels’s story was at least in part at Penrose’s behest.

I found myself wanting to hear more from the women in Penrose’s life. Penrose often saw himself following a current determined by these women. He came, for example, to believe his first wife had essentially trapped him in their relationship by falling for him.

Penrose never takes responsibility for any of his own actions towards the women in his life. So I wondered: how did they see it? What were their lives like? His ex-wife Joan (who died in 2019) and estranged wife Vanessa, who later became a mathematics teacher, both gave interviews for the book. But we learn little about their perspective on the man whose proclivities and career dominated their own lives.

One day there will be another biography of Penrose that will necessarily have distance from its subject because he will no longer be with us. The Impossible Man will be an important document for any future biographer, containing as it does such a close rendering of Penrose’s perspective on his own life.

The cost of genius

When it comes to describing Penrose’s contributions to mathematics and physics, the science writing, especially in the early pages, sings. Barss has a knack for writing up difficult ideas – whether it’s Penrose’s Nobel-prize-winning work on singularities or his attempt at quantum gravity, twistor theory. Overall, the luxurious prose makes the book highly readable.

Sometimes Barss indulges cosmic flourishes in a way that appears to reinforce Penrose’s perspective that the universe is happening to him rather than one over which he has any influence. In the end, I don’t know if we learn the cost of genius, but we certainly learn the cost of not recognizing that we are a part of the universe that has agency.

The final chapter is really Barss writing about himself and Penrose, and the conversations they have together. Penrose has macular degeneration now, so while both are on a visit to Perimeter in 2019, Barss reads some of his letters to Judith back to Penrose. Apparently, Penrose becomes quite emotional in a way that it seems no-one had ever seen – he weeps.

After that, he asks Barss to include the story about Judith. So, on some level, he knows he has erred.

The end of The Impossible Man is devastating. Barss describes how he eventually gains access to two of Penrose’s sons (three with Joan and one with Vanessa). In those interviews, he hears from children who have been traumatized by witnessing what they call “physical aggression” toward their mother. Even so, they both say they’d like to improve their relationship with their father.

Barss then asks a 92-year-old Penrose if he wants to patch things up with his family. His reply: “I feel my life is busy enough and if I get involved with them, it just distracts from other things.” As Barss concludes, Penrose is persistently unwilling to accept that in his life, he has been in the driver’s seat. He has had choices and doesn’t want to take responsibility for that. This, as much as Penrose’s intellectual interests and achievements, is the throughline of the text.

Penrose has shown that he doesn’t really care what others think, as long as he gets what he wants scientifically

The Penrose we meet at the end of The Impossible Man has shown that he doesn’t really care what others think, as long as he gets what he wants scientifically. It’s clear that Barss has a real affection for him, which makes his honesty about the Penrose he finds in the archives all the more remarkable. Perhaps motivated by generosity toward Penrose, Barss also lets the reader do a lot of the analysis.

I wonder, though, how many physicists who are steeped in this culture, and don’t concern themselves with gender equity issues, will miss how bad some of Penrose’s behaviour has been, as his colleagues at the time clearly did. The only documented objections to his behaviour seem more about him going off the deep end with his research into consciousness, cyclic theory and attacks on cosmic inflation.

As I worked on this review, I considered whether a different reviewer would have simply complained that the book has lots of stuff about Penrose’s personal messes that we don’t need to know. Maybe, to other readers, Penrose doesn’t come off quite as badly. For me, I prefer the hero I met in person rather than in the pages of this book. The Impossible Man is an important text, but it’s heartbreaking in the end.

- 2024 Basic Books (US)/Atlantic Books (UK) 352pp $32/£25hb

- In 2015 Physics World’s Tushna Commissariat interviewed Roger Penrose about his career. You can watch the video below

The post So you think you know Roger Penrose? Be prepared to be shocked appeared first on Physics World.

Solar cell greenhouse accelerates plant growth

Agrivoltaics is an interdisciplinary research area that lies at the intersection of photovoltaics (PVs) and agriculture. Traditional PV systems used in agricultural settings are made from silicon materials and are opaque. The opaque nature of these solar cells can block sunlight reaching plants and hinder their growth. As such, there’s a need for advanced semi-transparent solar cells that can provide sufficient power but still enable plants to grow instead of casting a shadow over them.

In a recent study headed up at the Institute for Microelectronics and Microsystems (IMM) in Italy, Alessandra Alberti and colleagues investigated the potential of semi-transparent perovskite solar cells as coatings on the roof of a greenhouse housing radicchio seedlings.

Solar cell shading an issue for plant growth

Opaque solar cells are known to induce shade avoidance syndrome in plants. This can cause morphological adaptations, including changes in chlorophyll content and an increased leaf area, as well as a change in the metabolite profile of the plant. Lower UV exposure can also reduce polyphenol content – antioxidant and anti-inflammatory molecules that humans get from plants.

Addressing these issues requires the development of semi-transparent PV panels with high enough efficiencies to be commercially feasible. Some common panels that can be made thin enough to be semi-transparent include organic and dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). While these have been used to provide power while growing tomatoes and lettuces, they typically only have a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of a few percent – a more efficient energy harvester is still required.

A semi-transparent perovskite solar cell greenhouse

Perovskite PVs are seen as the future of the solar cell industry and show a lot of promise in terms of PCE, even if they are not yet up to the level of silicon. However, perovskite PVs can also be made semi-transparent.

In this latest study, the researchers designed a laboratory-scale greenhouse using a semi-transparent europium (Eu)-enriched CsPbI3 perovskite-coated rooftop and investigated how radicchio seeds grew in the greenhouse for 15 days. They chose this Eu-enriched perovskite composition because CsPbI3 has superior thermal stability compared with other perovskites, making it ideal for long exposures to the Sun’s rays. The addition of Eu into the CsPbI3 structure improved the perovskite stability by minimizing the number of intrinsic defects and increasing the surface-to-volume ratio of perovskite grains.

Alongside this stability, this perovskite also has no volatile components that could potentially effuse under high surface temperatures. It also typically possesses a high PCE – the record for this composition is 21.15%, which is significantly higher and much more commercially feasible than previously possible with organic PVs and DSSCs. This perovskite, therefore, provides a good trade-off between the PCE that can be achieved while transmitting enough light to allow the seedlings to grow.

Low light conditions promote seedling growth

Even though the seedlings were exposed to lower light conditions than natural light, the team found that they grew more quickly, and with bigger leaves, than those under glass panels. This is attributed to the perovskite acting as a filter for only red light to pass through. And red light is known to improve the photosynthetic efficiency and light absorption capabilities of plants, as well as increase the levels of sucrose and hexose within the plant.

The researchers also found that seedlings grown under these conditions had different gene expression patterns compared with those grown under glass. These expression patterns were associated with environmental stress responses, growth regulation, metabolism and light perception, suggesting that the seedlings naturally adapted to different light conditions – although further research is needed to see whether these adaptations will improve the crop yield.

Overall, the use of perovskite PVs strikes a good balance between being able to provide enough power to cover the annual energy needs for irrigation, lighting and air conditioning, while still allowing the seedlings to grow – and grow much quicker and faster. The team suggest that the perovskite solar cells could help with indoor food production operations in the agricultural sector as a potentially affordable solution, although more work now needs to be done on much larger scales to test the technology’s commercial feasibility.

The research is published in Nature Communications.

The post Solar cell greenhouse accelerates plant growth appeared first on Physics World.

In Search of the Last Wild Axolotls

When the Dinos Died, Mammals Were Already Adopting Terrestrial Lifestyles

Doctor Behind Award-Winning Parkinson’s Research Among Scientists Purged From NIH

Space Volcanoes Tell the Explosive History of Mars, Venus, and Multiple Moons

Chicago-Sized Iceberg Breaks Away From Ice Sheet, Revealing Thriving Ecosystem

Stone Scrapers Found in China Shift Ideas on Paleolithic Tool Development

Stellarators, once fusion’s dark horse, hit their stride

I went to a physics conference—and a hockey game broke out

Trump administration purges U.S. health agency leaders

Intermittent Fasting Might Be an Easy Way to Boost Libido

MDA Space buys SatixFy to boost constellation production

Canada’s MDA Space announced plans April 1 to buy Israeli satellite chipmaker SatixFy in a $269 million deal to further vertically integrate its constellation manufacturing capabilities.

The post MDA Space buys SatixFy to boost constellation production appeared first on SpaceNews.

DESI delivers a cosmological bombshell

The first results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) are a cosmological bombshell, suggesting that the strength of dark energy has not remained constant throughout history. Instead, it appears to be weakening at the moment, and in the past it seems to have existed in an extreme form known as “phantom” dark energy.

The new findings have the potential to change everything we thought we knew about dark energy, a hypothetical entity that is used to explain the accelerating expansion of the universe.

“The subject needed a bit of a shake-up, and we’re now right on the boundary of seeing a whole new paradigm,” says Ofer Lahav, a cosmologist from University College London and a member of the DESI team.

DESI is mounted on the Nicholas U Mayall four-metre telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, and has the primary goal of shedding light on the “dark universe”. The term dark universe reflects our ignorance of the nature of about 95% of the mass–energy of the cosmos.

Intrinsic energy density

Today’s favoured Standard Model of cosmology is the lambda–cold dark matter (CDM) model. Lambda refers to a cosmological constant, which was first introduced by Albert Einstein in 1917 to keep the universe in a steady state by counteracting the effect of gravity. We now know that universe is expanding at an accelerating rate, so lambda is used to quantify this acceleration. It can be interpreted as an intrinsic energy density that is driving expansion. Now, DESI’s findings imply that this energy density is erratic and even more mysterious than previously thought.

DESI is creating a humungous 3D map of the universe. Its first full data release comprise 270 terabytes of data and was made public in March. The data include distance and spectral information about 18.7 million objects including 12.1 million galaxies and 1.6 million quasars. The spectral details of about four million nearby stars nearby are also included.

This is the largest 3D map of the universe ever made, bigger even than all the previous spectroscopic surveys combined. DESI scientists are already working with even more data that will be part of a second public release.

DESI can observe patterns in the cosmos called baryonic acoustic oscillations (BAOs). These were created after the Big Bang, when the universe was filled with a hot plasma of atomic nuclei and electrons. Density waves associated with quantum fluctuations in the Big Bang rippled through this plasma, until about 379,000 years after the Big Bang. Then, the temperature dropped sufficiently to allow the atomic nuclei to sweep up all the electrons. This froze the plasma density waves into regions of high mass density (where galaxies formed) and low density (intergalactic space). These density fluctuations are the BAOs; and they can be mapped by doing statistical analyses of the separation between pairs of galaxies and quasars.

The BAOs grow as the universe expands, and therefore they provide a “standard ruler” that allows cosmologists to study the expansion of the universe. DESI has observed galaxies and quasars going back 11 billion years in cosmic history.

nearby bright galaxies (yellow), luminous red galaxies (orange), emission-line galaxies (blue), and quasars (green). The inset shows the large-scale structure of a small portion of the universe. (Courtesy: Claire Lamman/DESI collaboration)

“What DESI has measured is that the distance [between pairs of galaxies] is smaller than what is predicted,” says team member Willem Elbers of the UK’s University of Durham. “We’re finding that dark energy is weakening, so the acceleration of the expansion of the universe is decreasing.”

As co-chair of DESI’s Cosmological Parameter Estimation Working Group, it is Elbers’ job to test different models of cosmology against the data. The results point to a bizarre form of “phantom” dark energy that boosted the expansion acceleration in the past, but is not present today.

The puzzle is related to dark energy’s equation of state, which describes the ratio of pressure of the universe to its energy density. In a universe with an accelerating expansion, the equation of state will have value that is less than about –1/3. A value of –1 characterizes the lambda–CDM model.

However, some alternative cosmological models allow the equation of state to be lower than –1. This means that the universe would expand faster than the cosmological constant would have it do. This points to a “phantom” dark energy that grew in strength as the universe expanded, but then petered out.

“It’s seems that dark energy was ‘phantom’ in the past, but it’s no longer phantom today,” says Elbers. “And that’s interesting because the simplest theories about what dark energy could be do not allow for that kind of behaviour.”

Dark energy takes over

The universe began expanding because of the energy of the Big Bang. We already know that for the first few billion years of cosmic history this expansion was slowing because the universe was smaller, meaning that the gravity of all the matter it contains was strong enough to put the brakes on the expansion. As the density decreased as the universe expanded, gravity’s influence waned and dark energy was able to take over. What DESI is telling us is that at the point that dark energy became more influential than matter, it was in its phantom guise.

“This is really weird,” says Lahav; and it gets weirder. The energy density of dark energy reached a peak at a redshift of 0.4, which equates to about 4.5 billion years ago. At that point, dark energy ceased its phantom behaviour and since then the strength of dark energy has been decreasing. The expansion of the universe is still accelerating, but not as rapidly. “Creating a universe that does that, which gets to a peak density and then declines, well, someone’s going to have to work out that model,” says Lahav.

Scalar quantum field

Unlike the unchanging dark-energy density described by the cosmological constant, a alternative concept called quintessence describes dark energy as a scalar quantum field that can have different values at different times and locations.

However, Elbers explains that a single field such as quintessence is incompatible with phantom dark energy. Instead, he says that “there might be multiple fields interacting, which on their own are not phantom but together produce this phantom equation of state,” adding that “the data seem to suggest that it is something more complicated.”

Before cosmology is overturned, however, more data are needed. On its own, the DESI data’s departure from the Standard Model of cosmology has a statistical significance 1.7σ. This is well below 5σ, which is considered a discovery in cosmology. However, when combined with independent observations of the cosmic microwave background and type Ia supernovae the significance jumps 4.2σ.

“Big rip” avoided

Confirmation of a phantom era and a current weakening would be mean that dark energy is far more complex than previously thought – deepening the mystery surrounding the expansion of the universe. Indeed, had dark energy continued on its phantom course, it would have caused a “big rip” in which cosmic expansion is so extreme that space itself is torn apart.

“Even if dark energy is weakening, the universe will probably keep expanding, but not at an accelerated rate,” says Elbers. “Or it could settle down in a quiescent state, or if it continues to weaken in the future we could get a collapse,” into a big crunch. With a form of dark energy that seems to do what it wants as its equation of state changes with time, it’s impossible to say what it will do in the future until cosmologists have more data.

Lahav, however, will wait until 5σ before changing his views on dark energy. “Some of my colleagues have already sold their shares in lambda,” he says. “But I’m not selling them just yet. I’m too cautious.”

The observations are reported in a series of papers on the arXiv server. Links to the papers can be found here.

The post DESI delivers a cosmological bombshell appeared first on Physics World.

‘The thrill of discovering something is a joy’: biophysicist Lisa Manning reflects on the surprising collaborations and intentional steps that have shaped her career

At a conference in 2014, bioengineer Jeffrey Fredberg of Harvard University presented pictures of asthma cells. To most people, the images would have been indistinguishable – they all showed tightly packed layers of cells from the airways of people with asthma. But as a physicist, Lisa Manning saw something no one else had spotted; she could tell, just by looking, that some of the model tissues were solid and some were fluid.

Animal tissues must be able to rearrange and flow but also switch to a state where they can withstand mechanical stress. However, whereas solid-liquid transitions are generally associated with a density change, many cellular systems, including asthma cells, can change from rigid to fluid-like at a constant packing density.

Many of a tissue’s properties depend on biochemical processes in its constituent cells, but some collective behaviours can be captured by mathematical models, which is the focus of Manning’s research. At the time, she was working with postdoctoral associate Dapeng Bi on a theory that a tissue’s rigidity depends on the shape of the cells, with cells in a rigid state touching more neighbouring cells than those in a fluid-like one. When she saw the pictures of the asthma cells she knew she was right. “That was a very cool moment,” she says.

Manning – now the William R Kenan, Jr Professor of Physics at Syracuse University in the US – began her research career in theoretical condensed-matter physics, completing a PhD at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2008. The thesis was on the mechanical properties of amorphous solids – materials that don’t have long-ranged order like a crystal but are nevertheless rigid. Amorphous solids include many plastics, soils and foods, but towards the end of her graduate studies, Manning started thinking about where else she could apply her work.

I was looking for a project where I could use some of the skills that I had been developing as a graduate student in an orthogonal way

“I was looking for a project where I could use some of the skills that I had been developing as a graduate student in an orthogonal way,” Manning recalls. Inspiration came from of a series of talks on tissue dynamics at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, where she recognized that the theories she had worked on could also apply to biological systems. “I thought it was amazing that you could apply physical principles to those systems,” she says.

The physics of life

Manning has been at Syracuse since completing a postdoc at Princeton University, and although she has many experimental collaborators, she is happy to still be a theorist. Whereas experimentalists in the biological sciences generally specialize in just one or two experimental models, she looks for “commonalities across a wide range of developmental systems”. That principle has led Manning to study everything from cancer to congenital disease and the development of embryos.

“In animal development, pretty universally one of the things that you must do is change from something that’s the shape of a ball of cells into something that is elongated,” says Manning, who working to understand how this happens. With collaborator Karen Kasza at Columbia University, she has demonstrated that rather than stretching as a solid, it’s energy efficient for embryos to change shape by undergoing a phase transition to a fluid, and many of their predictions have been confirmed in fruit fly embryo models.

More recently, Manning has been looking at how ideas from AI and machine learning can be applied to embryogenesis. Unlike most condensed-matter systems, tissues continuously tune individual interactions between cells, and it’s these localized forces that drive complex shape changes during embryonic development. Together with Andrea Liu of the University of Pennsylvania, Manning is now developing a framework that treats cell–cell interactions like weights in a neural network that can be adjusted to produce a desired outcome.

“I think you really need almost a new type of statistical physics that we don’t have yet to describe systems where you have these individually tunable degrees of freedom,” she says, “as opposed to systems where you have maybe one control parameter, like a temperature or a pressure.”

Developing the next generation

Manning’s transition to biophysics was spurred by an unexpected encounter with scientists outside her field. Between 2019 and 2023, she was director of the Bio-inspired Institute at Syracuse University, which supported similar opportunities for other researchers, including PhD students and postdocs. “As a graduate student, it’s a little easy to get focused on the one project that you know about, in the corner of the universe that your PhD is in,” she says.

As well as supporting science, one of the first things Manning spearheaded at the institute was a professional development programme for early-career researchers. “During our graduate schools, we’re typically mostly trained on how to do the academic stuff,” she says, “and then later in our careers, we’re expected to do a lot of other types of things like manage groups and manage funding.” To support their wider careers, participants in the programme build non-technical skills in areas such as project management, intellectual property and graphic design.

What I realized is that I did have implicit expectations that were based on my culture and background, and that they were distinct from those of some of my students

Manning’s senior role has also brought opportunities to build her own skills, with the COVID-19 pandemic in particular making her reflect and reevaluate how she approached mentorship. One of the appeals of academia is the freedom to explore independent research, but Manning began to see that her fear of micromanaging her students was sometimes creating confusion.

“What I realized is that I did have implicit expectations that were based on my culture and background, and that they were distinct from those of some of my students,” she says. “Because I didn’t name them, I was actually doing my students a disservice.” If she could give advice to her younger self, it would be that the best way to support early-career researchers as equals is to set clear expectations as soon as possible.

When Manning started at Syracuse, most of her students wanted to pursue research in academia, and she would often encourage them to think about other career options, such as working in industry. However, now she thinks academia is pereceived as the poorer choice. “Some students have really started to get this idea that academia is too challenging and it’s really hard and not at all great and not rewarding.”

Manning doesn’t want anyone to be put off pursuing their interests, and she feels a responsibility to be outspoken about why she loves her job. For her, the best thing about being a scientist is encapsulated by the moment with the asthma cells: “The thrill of discovering something is a joy,” she says, “being for just a moment, the only person in the world that understands something new.”

The post ‘The thrill of discovering something is a joy’: biophysicist Lisa Manning reflects on the surprising collaborations and intentional steps that have shaped her career appeared first on Physics World.

Who Was Cecilia Payne and How Did She Change Astronomy?

China launches internet technology test satellites with Long March 2D

China conducted a new launch for a nebulous series of internet technology test satellites early Tuesday.

The post China launches internet technology test satellites with Long March 2D appeared first on SpaceNews.

Yuval Noah Harari: ‘How Do We Share the Planet With This New Superintelligence?’

Apple picked as logo for celebration of classical physics in 2027

Physicists in the UK have drawn up plans for an International Year of Classical Physics (IYC) in 2027 – exactly three centuries after the death of Isaac Newton. Following successful international years devoted to astronomy (2009), light (2015) and quantum science (2025), they want more recognition for a branch of physics that underpins much of everyday life.

A bright green Flower of Kent apple has now been picked as the official IYC logo in tribute to Newton, who is seen as the “father of classical physics”. Newton, who died in 1727, famously developed our understanding of gravity – one of the fundamental forces of nature – after watching an apple fall from a tree of that variety in his home town of Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, in 1666.

“Gravity is central to classical physics and contributes an estimated $270bn to the global economy,” says Crispin McIntosh-Smith, chief classical physicist at the University of Lincoln. “Whether it’s rockets escaping Earth’s pull or skiing down a mountain slope, gravity is loads more important than quantum physics.”

McIntosh-Smith, who also works in cosmology having developed the Cosmic Crisp theory of the universe during his PhD, will now be leading attempts to get endorsement for IYC from the United Nations. He is set to take a 10-strong delegation from Bramley, Surrey, to Paris later this month.

An official gala launch ceremony is being pencilled in for the Travelodge in Grantham, which is the closest hotel to Newton’s birthplace. A parallel scientific workshop will take place in the grounds of Woolsthorpe Manor, with a plenary lecture from TV physicist Brian Cox. Evening entertainment will feature a jazz band.

Numerous outreach events are planned for the year, including the world’s largest demonstration of a wooden block on a ramp balanced by a crate on a pulley. It will involve schoolchildren pouring Golden Delicious apples into the crate to illustrate Newton’s laws of motion. Physicists will also be attempting to break the record for the tallest tower of stacked Braeburn apples.

But there is envy from those behind the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. “Of course, classical physics is important but we fear this year will peel attention away from the game-changing impact of quantum physics,” says Anne Oyd from the start-up firm Qrunch, who insists she will only play a cameo role in events. “I believe the impact of classical physics is over-hyped.”

The post Apple picked as logo for celebration of classical physics in 2027 appeared first on Physics World.