Robert P Crease lifts the lid on 25 years as a ‘science critic’

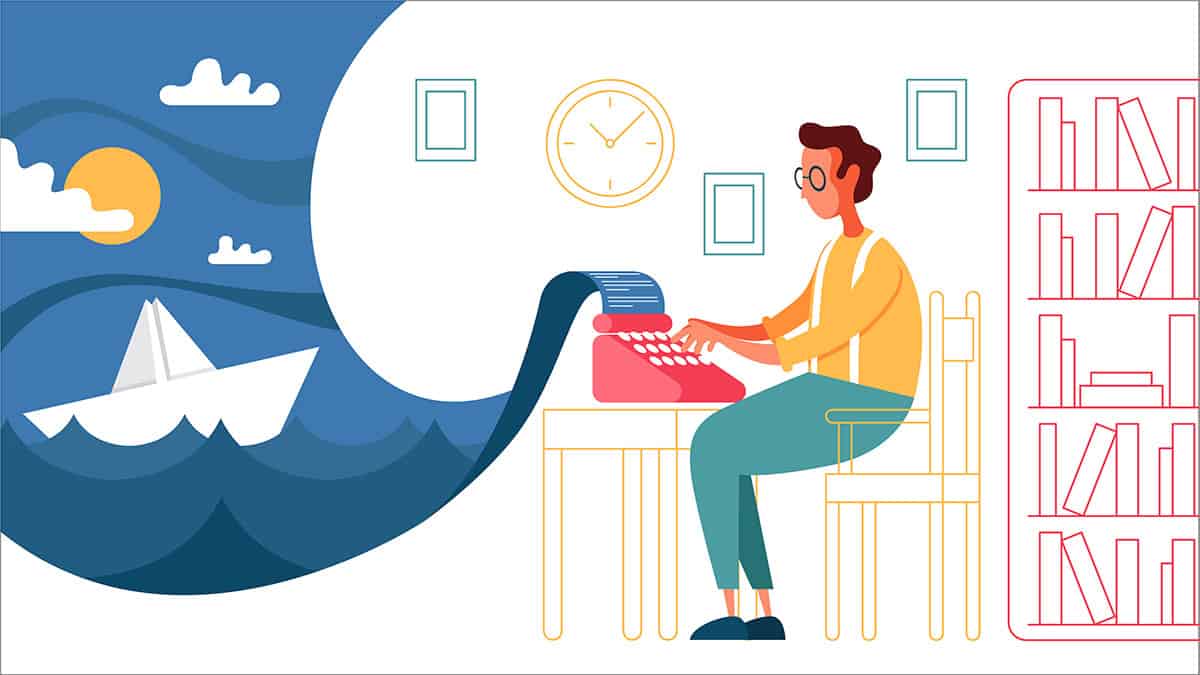

A quarter of a century ago, in May 2000, I published an article entitled “Why science thrives on criticism”. The article, which ran to slightly over a page in Physics World magazine, was the first in a series of columns called Critical Point. Periodicals, I said, have art and music critics as well as sports and political commentators, and book and theatre reviewers too. So why shouldn’t Physics World have a science critic?

The implication that I had a clear idea of the “critical point” for this series was not entirely accurate. As the years go by, I have found myself improvising, inspired by politics, books, scientific discoveries, readers’ thoughts, editors’ suggestions and more. If there is one common theme, it’s that science is like a workshop – or a series of loosely related workshops – as I argued in The Workshop and the World, a book that sprang from my columns.

Workshops are controlled environments, inside which researchers can stage and study special things – elementary particles, chemical reactions, plant uptakes of nutrients – that appear rarely or in a form difficult to study in the surrounding world. Science critics do not participate in the workshops themselves or even judge their activities. What they do is evaluate how workshops and worlds interact.

This can happen in three ways

Critical triangle

First is to explain why what’s going on inside the workshops matters to outsiders. Sometimes, those activities can be relatively simple to describe, which leads to columns concerning all manner of everyday activities. I have written, for example, about the physics of coffee and breadmaking. I’ve also covered toys, tops, kaleidoscopes, glass and other things that all of us – physicists and non-physicists alike – use, value and enjoy.

Sometimes I draw out more general points about why those activities are important. Early on, I invited readers to nominate their most beautiful experiments in physics. (Spoiler alert: the clear winner was the double-slit experiment with electrons.) I later did something similar about the cultural impact of equations – inviting readers to pick their favourites and reporting on their results (second spoiler alert: Maxwell’s equations came top). I also covered readers’ most-loved literature about laboratories.

Physicists often engage in activities that might seem inconsequential to them yet are an intrinsic part of the practice of physics

When viewing science as workshops, a second role is to explain why what’s outside the workshops matters to insiders. That’s because physicists often engage in activities that might seem inconsequential to them – they’re “just what the rest the world does” – yet are an intrinsic part of the practice of physics. I’ve covered, for example, physicists taking out patents, creating logos, designing lab architecture, taking holidays, organizing dedications, going on retirement and writing memorials for the deceased.

Such activities I term “black elephants”. That’s because they’re a cross between things physicists don’t want to talk about (“elephants in the room”) and things that force them to renounce cherished notions (just as “black swans” disprove that “all swans are white”).

A third role of a science critic is to explain what matters that takes place both inside and outside the workshop. I’m thinking of things like competition, leadership, trust, surprise, workplace training courses, cancel culture and even jokes and funny tales. Interpretations of the meaning of quantum mechanics, such as “QBism”, which I covered both in 2019 and 2022, are an ongoing interest. That’s because they’re relevant both to the structure of physics and to philosophy as they disrupt notions of realism, objectivity, temporality and the scientific method.

Being critical

The term “critic” may suggest someone with a congenitally negative outlook, but that’s wrong. My friend Fred Cohn, a respected opera critic, told me that, in a conversation after a concert, he criticized the performance of the singer Luciano Pavarotti. His remark provoked a woman to shout angrily at him: “Could you do better?” Of course not! It’s the critic’s role to evaluate performances of an activity, not to perform the activity oneself.

Having said that, sometimes a critic must be critical to be honest. In particular, I hate it when scientists try to delegitimize the experience of non-scientists by saying, for example, that “time does not exist”. Or when they pretend they don’t see rainbows but wavelengths of light or that they don’t see sunrises or the plane of a Foucault pendulum move but the Earth spinning. Comments like that turn non-scientists off science by making it seem elitist and other-worldly. It’s what I call “scientific gaslighting”.

Most of all, I hate it when scientists pontificate that philosophy is foolish or worthless, especially when it’s the likes of Steven Pinker, who ought to know better. Writing in Nature (518 300), I once criticized the great theoretical physicist Steven Weinberg, who I counted as a friend, for taking a complex and multivalent text, plucking out a single line, and misreading it as if the line were from a physics text.

The text in question was Plato’s Phaedo, where Socrates expresses his disappointment with his fellow philosopher Anaxagoras for giving descriptions of heavenly bodies “in purely physical terms, without regard to what is best”. Weinberg claimed this statement meant that Socrates “was not very interested in natural science”. Nothing could be further from the truth.

At that moment in the Phaedo, Socrates is recounting his intellectual autobiography. He has just come to the point where, as a youth, he was entranced by materialism and was eager to hear Anaxagoras’s opposing position. When Anaxagoras promised to describe the heavens both mechanically and as the product of a wise and divine mind but could do only the former, Socrates says he was disappointed.

Weinberg’s jibe ignores the context. Socrates is describing how he had once embraced Anaxagoras’s view of a universe ruled by a divine mind but later rejected that view. As an adult, Socrates learned to test hypotheses and other claims through putting them to the test, just as modern-day scientists do. Weinberg was misrepresenting Socrates by describing a position that he later abandoned.

The critical point of the critical point

Ultimately, the “critical point” of my columns over the last 25 years has been to provoke curiosity and excitement about what philosophers, historians and sociologists do for science. I’ve also wanted to raise awareness that these fields are not just fripperies but essential if we are to fully understand and protect scientific activity.

As I have explained several times – especially in the wake of the US shutting its High Flux Beam Reactor and National Tritium Labeling Facility – scientists need to understand and relate to the surrounding world with the insight of humanities scholars. Because if they don’t, they are in danger of losing their workshops altogether.

- Explore the best of Robert P Crease’s Critical Point articles in this special collection.

The post Robert P Crease lifts the lid on 25 years as a ‘science critic’ appeared first on Physics World.

.jpg)