Vue lecture

Did lead poisoning doom Neanderthals?

How Common Really Is Prostate Cancer and How Easy Is it to Get Tested?

Beyond the downlink: Why Earth-independent AI is the next moat in space operations

Every new space mission runs into the same wall: physics and fragility. Physics, because the speed of light and contested spectrum make real-time decision-making from the ground impossible when you need it most. Fragility, because modern space systems are software-defined, interconnected, and therefore exposed to radiation-induced faults, cascading anomalies and increasingly sophisticated cyber threats. The […]

The post Beyond the downlink: Why Earth-independent AI is the next moat in space operations appeared first on SpaceNews.

Beyond Gravity plans US push after fivefold boost in European solar mechanism output

Beyond Gravity is weighing expanding solar array drive mechanism production in Florida to support Golden Dome and other U.S. space projects, after doubling manufacturing space in Europe for hardware that keeps satellites pointed toward the sun.

The post Beyond Gravity plans US push after fivefold boost in European solar mechanism output appeared first on SpaceNews.

Polish space company Scanway Space secures U.S., European deals amid international expansion drive

WARSAW — The Polish optical systems manufacturer Scanway Space has secured its first order from an American company, in this case from Intuitive Machines for a multispectral telescope instrument to map the moon’s surface. Scanway CEO Jędrzej Kowalewski told SpaceNews the optical instrument, set to be launched in 2026, will allow Intuitive Machines to search […]

The post Polish space company Scanway Space secures U.S., European deals amid international expansion drive appeared first on SpaceNews.

Evo CT-Linac eases access to online adaptive radiation therapy

Adaptive radiation therapy (ART) is a personalized cancer treatment in which a patient’s treatment plan can be updated throughout their radiotherapy course to account for any anatomical variations – either between fractions (offline ART) or immediately prior to dose delivery (online ART). Using high-fidelity images to enable precision tumour targeting, ART improves outcomes while reducing side effects by minimizing healthy tissue dose.

Elekta, the company behind the Unity MR-Linac, believes that in time, all radiation treatments will incorporate ART as standard. Towards this goal, it brings its broad knowledge base from the MR-Linac to the new Elekta Evo, a next-generation CT-Linac designed to improve access to ART. Evo incorporates AI-enhanced cone-beam CT (CBCT), known as Iris, to provide high-definition imaging, while its Elekta ONE Online software automates the entire workflow, including auto-contouring, plan adaptation and end-to-end quality assurance.

A world first

In February of this year, Matthias Lampe and his team at the private centre DTZ Radiotherapy in Berlin, Germany became the first in the world to treat patients with online ART (delivering daily plan updates while the patient is on the treatment couch) using Evo. “To provide proper tumour control you must be sure to hit the target – for that, you need online ART,” Lampe tells Physics World.

The ability to visualize and adapt to daily anatomy enables reduction of the planning target volume, increasing safety for nearby organs-at-risk (OARs). “It is highly beneficial for all treatments in the abdomen and pelvis,” says Lampe. “My patients with prostate cancer report hardly any side effects.”

Lampe selected Evo to exploit the full flexibility of its C-arm design. He notes that for the increasingly prevalent hypofractionated treatments, a C-arm configuration is essential. “CT-based treatment planning and AI contouring opened up a new world for radiation oncologists,” he explains. “When Elekta designed Evo, they enabled this in an achievable way with an extremely reliable machine. The C-arm linac is the primary workhorse in radiotherapy, so you have the best of everything.”

Time considerations

While online ART can take longer than conventional treatments, Evo’s use of automation and AI limits the additional time requirement to just five minutes – increasing the overall workflow from 12 to 17 minutes and remaining within the clinic’s standard time slots.

The workflow begins with patient positioning and CBCT imaging, with Evo’s AI-enhanced Iris imaging significantly improving image quality, crucial when performing ART. The radiation therapist then matches the cone-beam and planning CTs and performs any necessary couch shift.

Simultaneously, Elekta ONE Online performs AI auto-contouring of OARs, which are reviewed by the physician, and the target volume is copied in. The physicist then simulates the dose distribution on the new contours, followed by a plan review. “Then you can decide whether to adapt or not,” says Lampe. “This is an outstanding feature.” The final stage is treatment delivery and online dosimetry.

When DTZ Berlin first began clinical treatments with Evo, some of Lampe’s colleagues were apprehensive as they were attached to the conventional workflow. “But now, with CBCT providing the chance to see what will be treated, every doctor on my team has embraced the shift and wouldn’t go back,” he says.

The first treatments were for prostate cancer, a common indication that’s relatively easy to treat. “I also thought that if the Elekta ONE workflow struggled, I could contour this on my own in a minute,” says Lampe. “But this was never necessary, the process is very solid. Now we also treat prostate cancer patients with lymph node metastases and those with relapse after radiotherapy. It’s a real success story.”

Lampe says that older and frailer patients may benefit the most from online ART, pointing out that while published studies often include relatively young, healthy patients, “our patients are old, they have chronic heart disease, they’re short of breath”.

For prostate cancer, for example, patients are instructed to arrive with a full bladder and an empty rectum. “But if a patient is in his eighties, he may not be able to do this and the volumes will be different every day,” Lampe explains. “With online adaptive, you can tell patients: ‘if this is not possible, we will handle it, don’t stress yourself’. They are very thankful.”

Making ART available to all

At UMC Utrecht in the Netherlands, the radiotherapy team has also added CT-Linac online adaptive to its clinical toolkit.

UMC Utrecht is renowned for its development of MR-guided radiotherapy, with physicists Bas Raaymakers and Jan Lagendijk pioneering the development of a hybrid MR-Linac. “We come from the world of MR-guidance, so we know that ART makes sense,” says Raaymakers. “But if we only offer MR-guided radiotherapy, we miss out on a lot of patients. We wanted to bring it to the wider community.”

At the time of speaking to Physics World, the team was treating its second patient with CBCT-guided ART, and had delivered about 30 fractions. Both patients were treated for bladder cancer, with future indications to explore including prostate, lung and breast cancers and bone metastases.

“We believe in ART for all patients,” says medical physicist Anette Houweling. “If you have MR and CT, you should be able to choose the optimal treatment modality based on image quality. For below the diaphragm, this is probably MR, while for the thorax, CT might be better.”

Ten minute target for OART

Houweling says that ART delivery has taken 19 minutes on average. “We record the CBCT, perform image fusion and then the table is moved, that’s all standard,” she explains. “Then the adaptive part comes in: delineation on the CBCT and creating a new plan with Elekta ONE Planning as part of Elekta One Online.”

The plan adaptation, when selected to perform, takes roughly four minutes to create a clinical-grade volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) plan. With the soon to be installed next-generation optimizer, it is expected to take less than one minute to generate a VMAT plan.

“As you start with the regular workflow, you can still decide not to choose adaptive treatment, and do a simple couch shift, up until the last second,” says Raaymakers. It’s very close to the existing workflow, which makes adoption easier. Also, the treatment slots are comparable to standard slots. Now with CBCT it takes 19 minutes and we believe we can get towards 10. That’s one of the drivers for cone-beam adaptive.”

Shorter treatment times will impact the decision as to which patients receive ART. If fully automated adaptive treatment is deliverable in a 10-minute time slot, it could be available to all patients. “From the physics side, our goal is to have no technological limitations to delivering ART. Then it’s up to the radiation oncologists to decide which patients might benefit,” Raaymakers explains.

Future gazing

Looking to the future, Raaymakers predicts that simulation-free radiotherapy will be adopted for certain standard treatments. “Why do you need days of preparation if you can condense the whole process to the moment when the patient is on the table,” he says. “That would be very much helped by online ART.”

“Scroll forward a few years and I expect that ART will be automated and fast such that the user will just sign off the autocontours and plan in one, maybe tune a little, and then go ahead,” adds Houweling. “That will be the ultimate goal of ART. Then there’s no reason to perform radiotherapy the traditional way.”

The post Evo CT-Linac eases access to online adaptive radiation therapy appeared first on Physics World.

Jesper Grimstrup’s The Ant Mill: could his anti-string-theory rant do string theorists a favour?

Imagine you had a bad breakup in college. Your ex-partner is furious and self-publishes a book that names you in its title. You’re so humiliated that you only dimly remember this ex, though the book’s details and anecdotes ring true.

According to the book, you used to be inventive, perceptive and dashing. Then you started hanging out with the wrong crowd, and became competitive, self-involved and incapable of true friendship. Your ex struggles to turn you around; failing, they leave. The book, though, is so over-the-top that by the end you stop cringing and find it a hoot.

That’s how I think most Physics World readers will react to The Ant Mill: How Theoretical High-energy Physics Descended into Groupthink, Tribalism and Mass Production of Research. Its author and self-publisher is the Danish mathematician-physicist Jesper Grimstrup, whose previous book was Shell Beach: the Search for the Final Theory.

After receiving his PhD in theoretical physics at the Technical University of Vienna in 2002, Grimstrup writes, he was “one of the young rebels” embarking on “a completely unexplored area” of theoretical physics, combining elements of loop quantum gravity and noncommutative geometry. But there followed a decade of rejected articles and lack of opportunities.

Grimstrup became “disillusioned, disheartened, and indignant” and in 2012 left the field, selling his flat in Copenhagen to finance his work. Grimstrup says he is now a “self-employed researcher and writer” who lives somewhere near the Danish capital. You can support him either through Ko-fi or Paypal.

Fomenting fear

The Ant Mill opens with a copy of the first page of the letter that Grimstrup’s fellow Dane Niels Bohr sent in 1917 to the University of Copenhagen successfully requesting a four-storey building for his physics institute. Grimstrup juxtaposes this incident with the rejection of his funding request, almost a century later, by the Danish Council for Independent Research.

Today, he writes, theoretical physics faces a situation “like the one it faced at the time of Niels Bohr”, but structural and cultural factors have severely hampered it, making it impossible to pursue promising new ideas. These include Grimstrup’s own “quantum holonomy theory, which is a candidate for a fundamental theory”. The Ant Mill is his diagnosis of how this came about.

The Standard Model of particle physics, according to Grimstrup, is dominated by influential groups that squeeze out other approaches.

A major culprit, in Grimstrup’s eyes, was the Standard Model of particle physics. That completed a structure for which theorists were trained to be architects and should have led to the flourishing of a new crop of theoretical ideas. But it had the opposite effect. The field, according to Grimstrup, is now dominated by influential groups that squeeze out other approaches.

The biggest and most powerful is string theory, with loop quantum gravity its chief rival. Neither member of the coterie can make testable predictions, yet because they control jobs, publications and grants they intimidate young researchers and create what Grimstrup calls an “undercurrent of fear”. (I leave assessment of this claim to young theorists.)

Half the chapters begin with an anecdote in which Grimstrup describes an instance of rejection by a colleague, editor or funding agency. In the book’s longest chapter Grimstrup talks about his various rejections – by the Carlsberg Foundation, The European Physics Journal C, International Journal of Modern Physics A, Classical and Quantum Gravity, Reports on Mathematical Physics, Journal of Geometry and Physics, and the Journal of Noncommutative Geometry.

Grimstrup says that the reviewers and editors of these journals told him that his papers variously lacked concrete physical results, were exercises in mathematics, seemed the same as other papers, or lacked “relevance and significance”. Grimstrup sees this as the coterie’s handiwork, for such journals are full of string theory papers open to the same criticism.

“Science is many things,” Grimstrup writes at the end. “[S]imultaneously boring and scary, it is both Indiana Jones and anonymous bureaucrats, and it is precisely this diversity that is missing in the modern version of science”. What the field needs is “courage…hunger…ambition…unwillingness to compromise…anarchy.”

Grimstrup hopes that his book will have an impact, helping to inspire young researchers to revolt, and to make all the scientific bureaucrats and apparatchiks and bookkeepers and accountants “wake up and remember who they truly are”.

The critical point

The Ant Mill is an example of what I have called “rant literature” or rant-lit. Evangelical, convinced that exposing truth will make sinners come to their senses and change their evil ways, rant lit can be fun to read, for it is passionate and full of florid metaphors.

Theoretical physicists, Grimstrup writes, have become “obedient idiots” and “technicians”. He slams theoretical physics for becoming a “kingdom”, a “cult”, a “hamster wheel”, and “ant mill”, in which the ants march around in a pre-programmed “death spiral”.

Grimstrup hammers away at theories lacking falsifiability, but his vehemence invites you to ask: “Is falsifiability really the sole criterion for deciding whether to accept or fail to pursue a theory?”

An attentive reader, however, may come away with a different lesson. Grimstrup calls falsifiability the “crown jewel of the natural sciences” and hammers away at theories lacking it. But his vehemence invites you to ask: “Is falsifiability really the sole criterion for deciding whether to accept or fail to pursue a theory?”

In his 2013 book String Theory and the Scientific Method, for instance, the Stockholm University philosopher of science Richard Dawid suggested rescuing the scientific status of string theory by adding such non-empirical criteria to evaluating theories as clarity, coherence and lack of alternatives. It’s an approach that both rescues the formalistic approach to the scientific method and undermines it.

Dawid, you see, is making the formalism follow the practice rather than the other way around. In other words, he is able to reformulate how we make theories because he already knows how theorizing works – not because he only truly knows what it is to theorize after he gets the formalism right.

Grimstrup’s rant, too, might remind you of the birth of the Yang–Mills theory in 1954. Developed by Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills, it was a theory of nuclear binding that integrated much of what was known about elementary particle theory but implied the existence of massless force-carrying particles that then were known not to exist. In fact, at one seminar Wolfgang Pauli unleashed a tirade against Yang for proposing so obviously flawed a theory.

The theory, however, became central to theoretical physics two decades later, after theorists learned more about the structure of the world. The Yang-Mills story, in other words, reveals that theory-making does not always conform to formal strictures and does not always require a testable prediction. Sometimes it just articulates the best way to make sense of the world apart from proof or evidence.

The lesson I draw is that becoming the target of a rant might not always make you feel repentant and ashamed. It might inspire you into deep reflection on who you are in a way that is insightful and vindicating. It might even make you more rather than less confident about why you’re doing what you’re doing

Your ex, of course, would be horrified.

The post Jesper Grimstrup’s <em>The Ant Mill</em>: could his anti-string-theory rant do string theorists a favour? appeared first on Physics World.

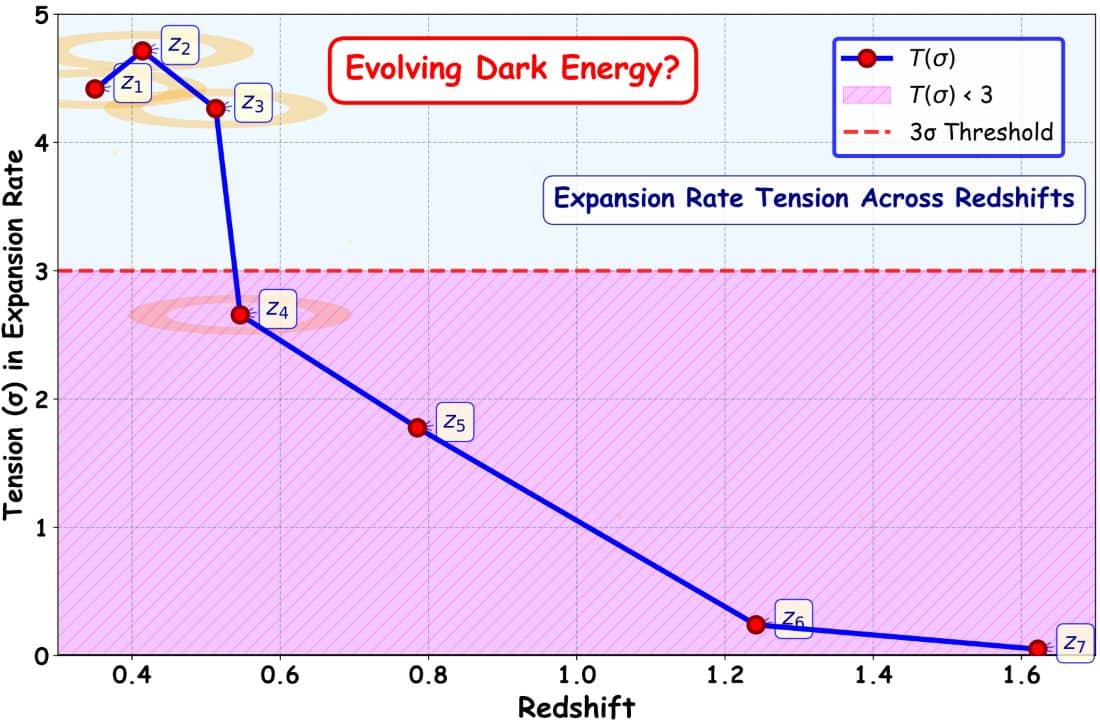

Further evidence for evolving dark energy?

The term dark energy, first used in 1998, is a proposed form of energy that affects the universe on the largest scales. Its primary effect is to drive the accelerating expansion of the universe – an observation that was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Dark energy is now a well established concept and forms a key part of the standard model of Big Bang cosmology, the Lambda-CDM model.

The trouble is, we’ve never really been able to explain exactly what dark energy is, or why it has the value that it does.

Even worse, new data acquired by cutting-edge telescopes have suggested that dark energy might not even exist as we had imagined it.

This is where the new work by Mukherjee and Sen comes in. They combined two of these datasets, while making as few assumptions as possible, to understand what’s going on.

The first of these datasets came from baryon acoustic oscillations. These are patterns in the distribution of matter in the universe, created by sound waves in the early universe.

The second dataset is based on a survey of supernovae data from the last 5 years. Both sets of data can be used to track the expansion history of the universe by measuring distances at different snapshots in time.

The team’s results are in tension with the Lambda-CDM model at low redshifts. Put simply, the results disagree with the current model at recent times. This provides further evidence for the idea that dark energy, previously considered to have a constant value, is evolving over time.

The is far from the end of the story with dark energy. New observational data, and new analyses such as this one are urgently required to provide a clearer picture.

However, where there’s uncertainty, there’s opportunity. Understanding dark energy could hold the key to understanding quantum gravity, the Big Bang and the ultimate fate of the universe.

Read the full article

Mukherjee and Sen et al. 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 098401

The post Further evidence for evolving dark energy? appeared first on Physics World.

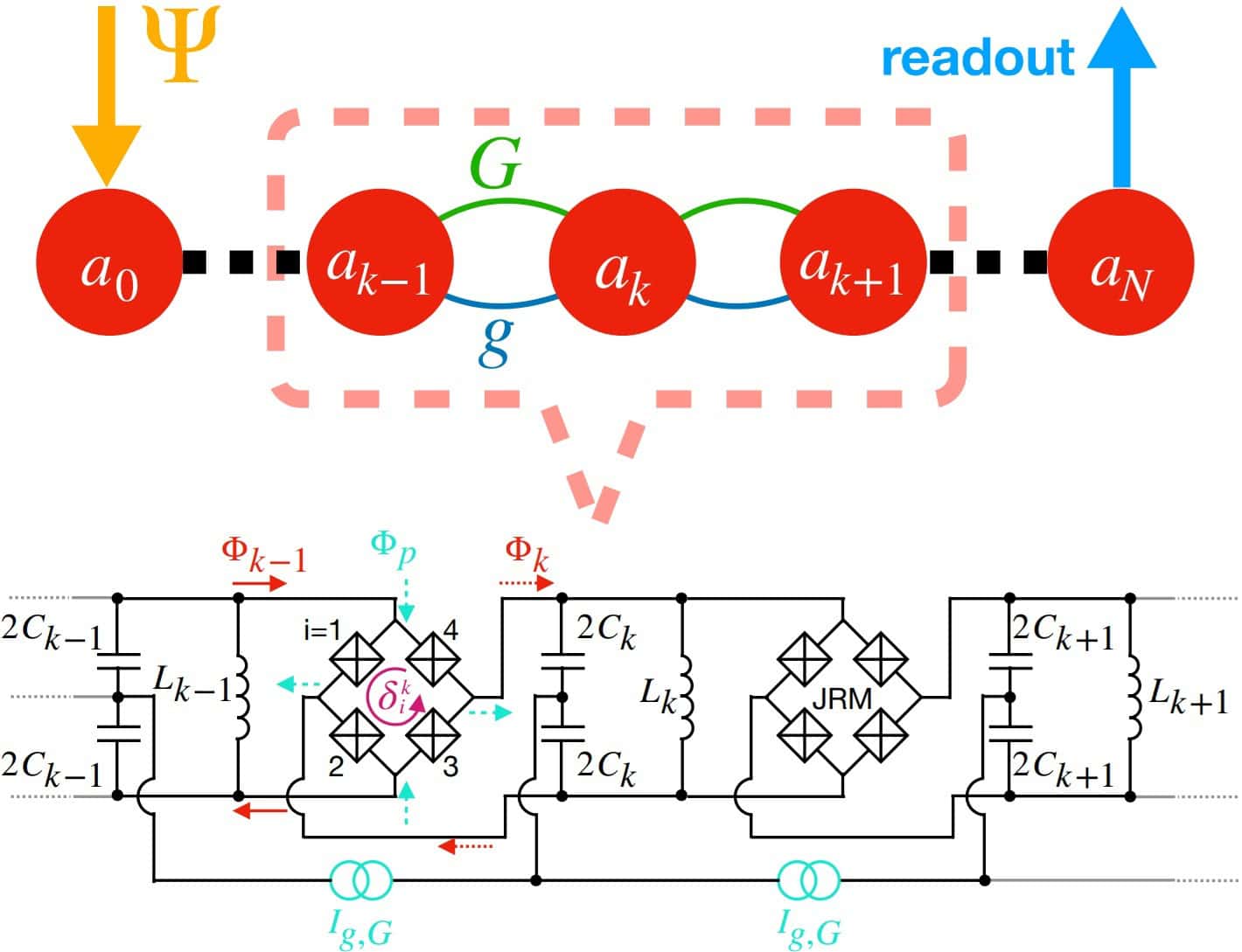

Searching for dark matter particles

Dark matter is hypothesised form of matter that does not emit, absorb, or reflect light, making it invisible to electromagnetic observations. Although we have never detected it, its existence is inferred from its gravitational effects on visible matter and the large-scale structure of the universe.

The Standard Model of particle physics does not contain any dark matter particles but there have been several proposed extensions of how they might be included. Several of these are very low mass particles such as the axion or the sterile neutrino.

Detecting these hypothesised particles is very challenging, however, due to the extreme sensitivity required.

Electromagnetic resonant systems, such as cavities and LC circuits, are widely used for this purpose, as well as to detect high-frequency gravitational waves.

When an external signal matches one of these systems’ resonant frequencies, the system responds with a large amplitude, making the signal possible to detect. However, there is always a trade-off between the sensitivity of the detector and the range of frequencies it is able to detect (its bandwidth).

A natural way to overcome this compromise is to consider multi-mode resonators, which can be viewed as coupled networks of harmonic oscillators. Their scan efficiency can be significantly enhanced beyond the standard quantum limit of simple single-mode resonators.

In a recent paper, the researchers demonstrated how multi-mode resonators can achieve the advantages of both sensitive and broadband detection. By connecting adjacent modes inside the resonant cavity, and tuning these interactions to comparable magnitudes, off-resonant (i.e. unwanted) frequency shifts are effectively cancelled increasing the overall response of the system.

Their method allows us to search for these elusive dark matter particles in a faster, more efficient way.

Read the full article

Chen et al. 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 057601

The post Searching for dark matter particles appeared first on Physics World.

SpaceX’s Second-Gen Starship Signs Off With a Near-Perfect Test Flight

Physicists explain why some fast-moving droplets stick to hydrophobic surfaces

What happens when a microscopic drop of water lands on a water-repelling surface? The answer is important for many everyday situations, including pesticides being sprayed on crops and the spread of disease-causing aerosols. Naively, one might expect it to depend on the droplet’s speed, with faster-moving droplets bouncing off the surface and slower ones sticking to it. However, according to new experiments, theoretical work and simulations by researchers in the UK and the Netherlands, it’s more complicated than that.

“If the droplet moves too slowly, it sticks,” explains Jamie McLauchlan, a PhD student at the University of Bath, UK who led the new research effort with Bath’s Adam Squires and Anton Souslov of the University of Cambridge. “Too fast, and it sticks again. Only in between is bouncing possible, where there is enough momentum to detach from the surface but not so much that it collapses back onto it.”

As well as this new velocity-dependent condition, the researchers also discovered a size effect in which droplets that are too small cannot bounce, no matter what their speed. This size limit, they say, is set by the droplets’ viscosity, which prevents the tiniest droplets from leaving the surface once they land on it.

Smaller-sized, faster-moving droplets

While academic researchers and industrialists have long studied single-droplet impacts, McLauchlan says that much of this earlier work focused on millimetre-sized drops that took place on millisecond timescales. “We wanted to push this knowledge to smaller sizes of micrometre droplets and faster speeds, where higher surface-to-volume ratios make interfacial effects critical,” he says. “We were motivated even further during the COVID-19 pandemic, when studying how small airborne respiratory droplets interact with surfaces became a significant concern.”

Working at such small sizes and fast timescales is no easy task, however. To record the outcome of each droplet landing, McLauchlan and colleagues needed a high-speed camera that effectively slowed down motion by a factor of 100 000. To produce the droplets, they needed piezoelectric droplet generators capable of dispensing fluid via tiny 30-micron nozzles. “These dispensers are highly temperamental,” McLauchlan notes. “They can become blocked easily by dust and fibres and fail to work if the fluid viscosity is too high, making experiments delicate to plan and run. The generators are also easy to break and expensive.”

Droplet modelled as a tiny spring

The researchers used this experimental set-up to create and image droplets between 30‒50 µm in diameter as they struck water-repelling surfaces at speeds of 1‒10 m/s. They then compared their findings with calculations based on a simple mathematical model that treats a droplet like a tiny spring, taking into account three main parameters in addition to its speed: the stickiness of the surface; the viscosity of the droplet liquid; and the droplet’s surface tension.

Previous research had shown that on perfectly non-wetting surfaces, bouncing does not depend on velocity. Other studies showed that on very smooth surfaces, droplets can bounce on a thin air layer. “Our work has explored a broader range of hydrophobic surfaces, showing that bouncing occurs due to a delicate balance of kinetic energy, viscous dissipation and interfacial energies,” McLauchlan tells Physics World.

This is exciting, he adds, because it reveals a previously unexplored regime for bounce behaviour: droplets that are too small, or too slow, will always stick, while sufficiently fast droplets can rebound. “This finding provides a general framework that explains bouncing at the micron scale, which is directly relevant for aerosol science,” he says.

A novel framework for engineering microdroplet processes

McLauchlan thinks that by linking bouncing to droplet velocity, size and surface properties, the new framework could make it easier to engineer microdroplets for specific purposes. “In agriculture, for example, understanding how spray velocities interact with plant surfaces with different hydrophobicity could help determine when droplets deposit fully versus when they bounce away, improving the efficiency of crop spraying,” he says.

Such a framework could also be beneficial in the study of airborne diseases, since exhaled droplets frequently bump into surfaces while floating around indoors. While droplets that stick are removed from the air, and can no longer transmit disease via that route, those that bounce are not. Quantifying these processes in typical indoor environments will provide better models of airborne pathogen concentrations and therefore disease spread, McLauchlan says. For example, in healthcare settings, coatings could be designed to inhibit or promote bouncing, ensuring that high-velocity respiratory droplets from sneezes either stick to hospital surfaces or recoil from them, depending on which mode of potential transmission (airborne or contact-based) is being targeted.

The researchers now plan to expand their work on aqueous droplets to droplets with more complex soft-matter properties. “This will include adding surfactants, which introduce time-dependent surface tensions, and polymers, which give droplets viscoelastic properties similar to those found in biological fluids,” McLauchlan reveals. “These studies will present significant experimental challenges, but we hope they broaden the relevance of our findings to an even wider range of fields.”

The present work is detailed in PNAS.

The post Physicists explain why some fast-moving droplets stick to hydrophobic surfaces appeared first on Physics World.

Chicago’s beloved ‘rat hole’ was actually made by a squirrel

Ancient chewing gum could reveal how early men and women split up their chores

Whiplash at CDC as hundreds of employees are terminated, then reinstated

Rocket Lab launches seventh Synspective radar imaging satellite

Rocket Lab launched a spacecraft for one Japanese radar imaging company Oct. 14, just days after signing a contract for additional launches for another.

The post Rocket Lab launches seventh Synspective radar imaging satellite appeared first on SpaceNews.

Why Do Whales and Dolphins Beach Themselves, and Is Dementia to Blame?

A Growing Weak Spot in Earth's Magnetic Field May Cause More Satellites to Short Circuit

A Quarter of the CDC Is Gone

Hippos Lived Alongside Mammoths 47,000 Years Ago During the Last Ice Age

How People With ADHD Can Harness Mind Wandering and Enhance Creativity

Ancient Romans Gave Tiny Bronze Skeletons to Party Guests As a Morbid Reminder to Live Life

Viasat and Space42’s D2D joint venture finds first mobile partner in UAE

Equatys, the U.S.-based Viasat and Emirati satellite operator Space42’s shared space infrastructure joint venture for direct-to-device services, has gained its first mobile network partner as it seeks to challenge SpaceX’s growing lead in the emerging market.

The post Viasat and Space42’s D2D joint venture finds first mobile partner in UAE appeared first on SpaceNews.

Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS Is Spewing Water Like a Cosmic Fire Hydrant