The Future Circular Collider is unduly risky – CERN needs a ‘Plan B’

Last November I visited the CERN particle-physics lab near Geneva to attend the 4th International Symposium on the History of Particle Physics, which focused on advances in particle physics during the 1980s and 1990s. As usual, it was a refreshing, intellectually invigorating visit. I’m always inspired by the great diversity of scientists at CERN – complemented this time by historians, philosophers and other scholars of science.

As noted by historian John Krige in his opening keynote address, “CERN is a European laboratory with a global footprint. Yet for all its success it now faces a turning point.” During the period under examination at the symposium, CERN essentially achieved the “world laboratory” status that various leaders of particle physics had dreamt of for decades.

By building the Large Electron Positron (LEP) collider and then the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the latter with contributions from Canada, China, India, Japan, Russia, the US and other non-European nations, CERN has attracted researchers from six continents. And as the Cold War ended in 1989–1991, two prescient CERN staff members developed the World Wide Web, helping knit this sprawling international scientific community together and enable extensive global collaboration.

The LHC was funded and built during a unique period of growing globalization and democratization that emerged in the wake of the Cold War’s end. After the US terminated the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, CERN was the only game in town if one wanted to pursue particle physics at the multi-TeV energy frontier. And many particle physicists wanted to be involved in the search for the Higgs boson, which by the mid-1990s looked as if it should show up at accessible LHC energies.

Having discovered this long-sought particle at the LHC in 2012, CERN is now contemplating an ambitious construction project, the Future Circular Collider (FCC). Over three times larger than the LHC, it would study this all-important, mass-generating boson in greater detail using an electron–positron collider dubbed FCC-ee, estimated to cost $18bn and start operations by 2050.

Later in the century, the FCC-hh, a proton–proton collider, would go in the same tunnel to see what, if anything, may lie at much higher energies. That collider, the cost of which is currently educated guesswork, would not come online until the mid 2070s.

But the steadily worsening geopolitics of a fragmenting world order could make funding and building these colliders dicey affairs. After Russia’s expulsion from CERN, little in the way of its contributions can be expected. Chinese physicists had hoped to build an equivalent collider, but those plans seem to have been put on the backburner for now.

And the “America First” political stance of the current US administration is hardly conducive to the multibillion-dollar contribution likely required from what is today the world’s richest (albeit debt-laden) nation. The ongoing collapse of the rules-based world order was recently put into stark relief by the US invasion of Venezuela and abduction of its president Nicolás Maduro, followed by Donald Trump’s menacing rhetoric over Greenland.

While these shocking events have immediate significance for international relations, they also suggest how difficult it may become to fund gargantuan international scientific projects such as the FCC. Under such circumstances, it is very difficult to imagine non-European nations being able to contribute a hoped-for third of the FCC’s total costs.

But the mounting European populist right-wing parties are no great friends of physics either, nor of international scientific endeavours. And Europeans face the not-insignificant costs of military rearmament in the face of Russian aggression and likely US withdrawal from Europe.

So the other two thirds of the FCC’s many billions in costs cannot be taken for granted – especially not during the decades needed to construct its 91 km tunnel, 350 GeV electron–positron collider, the subsequent 100 TeV proton collider, and the massive detectors both machines require.

According to former CERN director-general Chris Llewellyn Smith in his symposium lecture, “The political history of the LHC“, just under 12% of the material project costs of the LHC eventually came from non-member nations. It therefore warps the imagination to believe that a third of the much greater costs of the FCC can come from non-member nations in the current “Wild West” geopolitical climate.

But particle physics desperately needs a Higgs factory. After the 1983 Z boson discovery at the CERN SPS Collider, it took just six years before we had not one but two Z factories – LEP and the Stanford Linear Collider – which proved very productive machines. It’s now been more than 13 years since the Higgs boson discovery. Must we wait another 20 years?

Other options

CERN therefore needs a more modest, realistic, productive new scientific facility – a “Plan B” – to cope with the geopolitical uncertainties of an imperfect, unpredictable world. And I was encouraged to learn that several possible ideas are under consideration, according to outgoing CERN director-general Fabiola Gianotti in her symposium lecture, “CERN today and tomorrow“.

Three of these ideas reflect the European Strategy for Particle Physics, which states that “an electron–positron Higgs factory is the highest-priority next CERN collider”. Two linear electron–positron colliders would require just 11–34 km of tunnelling and could begin construction in the mid-2030s, but would involve a fair amount of technical risk and cost roughly €10bn.

The least costly and risky option, dubbed LEP3, involves installing superconducting radio-frequency cavities in the existing LHC tunnel once the high-luminosity proton run ends. Essentially an upgrade of the 200 GeV LEP2, this approach is based on well-understood technologies and would cost less than €5bn but can reach at most 240 GeV. The linear colliders could attain over twice that energy, enabling research on Higgs-boson decays into top quarks and the triple-Higgs self-interaction.

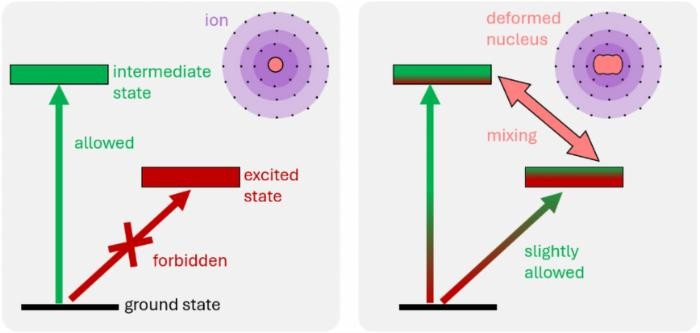

Other proposed projects involving the LHC tunnel can produce large numbers of Higgs bosons with relatively minor backgrounds, but they can hardly be called “Higgs factories”. One of these, dubbed the LHeC, could only produce a few thousand Higgs bosons annually and would allow other important research on proton structure functions. Another idea is the proposed Gamma Factory, in which laser beams would be backscattered from LHC beams of partially stripped ions. If sufficient photon energies and intensity can be achieved, it will allow research on the γγ → H interaction. These alternatives would cost at most a few billion euros.

As Krige stressed in his keynote address, CERN was meant to be more than a scientific laboratory at which European physicists could compete with their US and Soviet counterparts. As many of its founders intended, he said, it was “a cultural weapon against all forms of bigoted nationalism and anti-science populism that defied Enlightenment values of critical reasoning”. The same logic holds true today.

In planning the next phase in CERN’s estimable history, it is crucial to preserve this cultural vitality, while of course providing unparalleled opportunities to do world-class science – lacking which, the best scientists will turn elsewhere.

I therefore urge CERN planners to be daring but cognizant of financial and political reality in the fracturing world order. Don’t for a nanosecond assume that the future will be a smooth extrapolation from the past. Be fairly certain that whatever new facility you decide to build, there is a solid financial pathway to achieving it in a reasonable time frame.

The future of CERN – and the bracing spirit of CERN – rests in your hands.

The post The Future Circular Collider is unduly risky – CERN needs a ‘Plan B’ appeared first on Physics World.