What shape is a uranium nucleus?

High-energy heavy-nuclei collisions, conducted at particle colliders such as CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and BNL’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) are able to produce a state of matter called a quark-gluon plasma (QGP).

A QGP is believed to have existed just after the Big Bang. The building blocks of protons and neutrons – quarks and gluons – were not confined inside particles as usual but instead formed a hot, dense, strongly interacting soup.

Studying this state of matter helps us understand the strong nuclear force, the early universe, and how matter evolved into the forms we see today.

In order to understand QGP created in a particle collider you need to know the initial conditions. In this case that is the shape and structure of the heavy nuclei that collided.

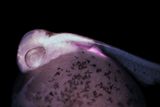

A major complicating factor here is that most atomic nuclei are deformed. They are not spherical but rather squashed and ellipsoidal or even pear-shaped.

Collisions of deformed nuclei with different orientations brings in a large amount of randomness and therefore hinders our ability to describe the initial conditions of the QGP.

A new method called imaging-by-smashing was developed by the STAR experiment at RHIC, where atomic nuclei are smashed together at extremely high speeds. By studying the patterns in the debris from these collisions, researchers can infer the original shape of the nuclei.

In this latest study, they compared collisions between two types of nuclei: uranium-238, which has a strongly deformed shape, and gold-197, which is nearly spherical.

The differences between uranium and gold helped isolate the effects of uranium’s deformation. Their results matched predictions from advanced hydrodynamic simulations and earlier low-energy experiments.

Most interestingly, they found hints that uranium might possess a pear-like (octupole) shape, in addition to its dominant football-like (quadrupole) shape. This feature had not previously been observed in high-energy collisions

This method is still new, but in the future, it could give us key insights nuclear structure throughout the periodic table. These measurements probe nuclei at energy scales orders of magnitudes higher than traditional methods, potentially revealing how nuclear structure evolves across very different energy regimes.

Read the full article

The STAR Collaboration, 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 108601

The post What shape is a uranium nucleus? appeared first on Physics World.