Reinforcement learning could help airborne wind energy take off

When people think of wind energy, they usually think of windmill-like turbines dotted among hills or lined up on offshore platforms. But there is also another kind of wind energy, one that replaces stationary, earthbound generators with tethered kites that harvest energy as they soar through the sky.

This airborne form of wind energy, or AWE, is not as well-developed as the terrestrial version, but in principle it has several advantages. Power-generating kites are much less massive than ground-based turbines, which reduces both their production costs and their impact on the landscape. They are also far easier to install in areas that lack well-developed road infrastructure. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, wind speeds are many times greater at high altitudes than they are near the ground, significantly enhancing the power densities available for kites to harvest.

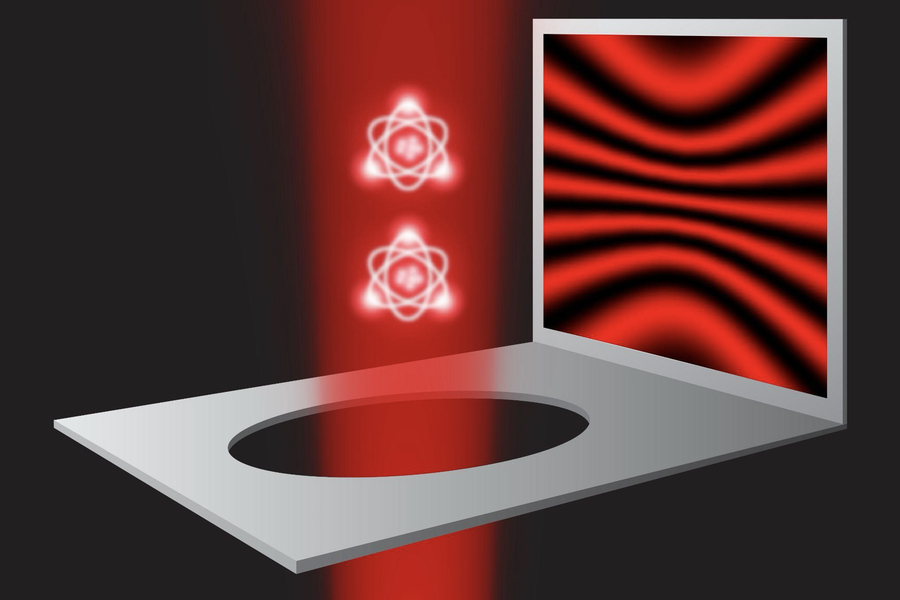

There is, however, one major technical challenge for AWE, and it can be summed up in a single word: control. AWE technology is operationally more complex than conventional turbines, and the traditional method of controlling kites (known as model-predictive control) struggles to adapt to turbulent wind conditions. At best, this reduces the efficiency of energy generation. At worst, it makes it challenging to keep devices safe, stable and airborne.

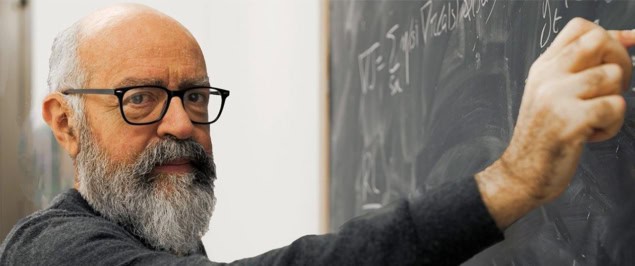

In a paper published in EPL, Antonio Celani and his colleagues Lorenzo Basile and Maria Grazia Berni of the University of Trieste, Italy, and the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) propose an alternative control method based on reinforcement learning. In this form of machine learning, an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with its environment and receiving feedback in the form of “rewards” for good performance. This form of control, they say, should be better at adapting to the variable and uncertain conditions that power-generating kites encounter while airborne.

What was your motivation for doing this work?

Our interest originated from some previous work where we studied a fascinating bird behaviour called thermal soaring. Many birds, from the humble seagull to birds of prey and frigatebirds, exploit atmospheric currents to rise in the sky without flapping their wings, and then glide or swoop down. They then repeat this cycle of ascent and descent for hours, or even for weeks if they are migratory birds. They’re able to do this because birds are very effective at extracting energy from the atmosphere to turn it into potential energy, even though the atmospheric flow is turbulent, hence very dynamic and unpredictable.

In those works, we showed that we could use reinforcement learning to train virtual birds and also real toy gliders to soar. That got us wondering whether this same approach could be exported to AWE.

When we started looking at the literature, we saw that in most cases, the goal was to control the kite to follow a predetermined path, irrespective of the changing wind conditions. These cases typically used only simple models of atmospheric flow, and almost invariably ignored turbulence.

This is very different from what we see in birds, which adapt their trajectories on the fly depending on the strength and direction of the fluctuating wind they experience. This led us to ask: can a reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm discover efficient, adaptive ways of controlling a kite in a turbulent environment to extract energy for human consumption?

What is the most important advance in the paper?

We offer a proof of principle that it is indeed possible to do this using a minimal set of sensor inputs and control variables, plus an appropriately designed reward/punishment structure that guides trial-and-error learning. The algorithm we deploy finds a way to manoeuvre the kite such that it generates net energy over one cycle of operation. Most importantly, this strategy autonomously adapts to the ever-fluctuating conditions induced by turbulence.

The main point of RL is that it can learn to control a system just by interacting with the environment, without requiring any a priori knowledge of the dynamical laws that rule its behaviour. This is extremely useful when the systems are very complex, like the turbulent atmosphere and the aerodynamics of a kite.

What are the barriers to implementing RL in real AWE kites, and how might these barriers be overcome?

The virtual environment that we use in our paper to train the kite controller is very simplified, and in general the gap between simulations and reality is wide. We therefore regard the present work mostly as a stimulus for the AWE community to look deeper into alternatives to model-predictive control, like RL.

On the physics side, we found that some phases of an AWE generating cycle are very difficult for our system to learn, and they require a painful fine-tuning of the reward structure. This is especially true when the kite is close to the ground, where winds are weaker and errors are the most punishing. In those cases, it might be a wise choice to use other heuristic, hard-wired control strategies rather than RL.

Finally, in a virtual environment like the one we used to do the RL training in this work, it is possible to perform many trials. In real power kites, this approach is not feasible – it would take too long. However, techniques like offline RL might resolve this issue by interleaving a few field experiments where data are collected with extensive off-line optimization of the strategy. We successfully used this approach in our previous work to train real gliders for soaring.

What do you plan to do next?

We would like to explore the use of offline RL to optimize energy production for a small, real AWE system. In our opinion, the application to low-power systems is particularly relevant in contexts where access to the power grid is limited or uncertain. A lightweight, easily portable device that can produce even small amounts of energy might make a big difference in the everyday life of remote, rural communities, and more generally in the global south.

The post Reinforcement learning could help airborne wind energy take off appeared first on Physics World.