Helgoland 2025: the inside story of what happened on the ‘quantum island’

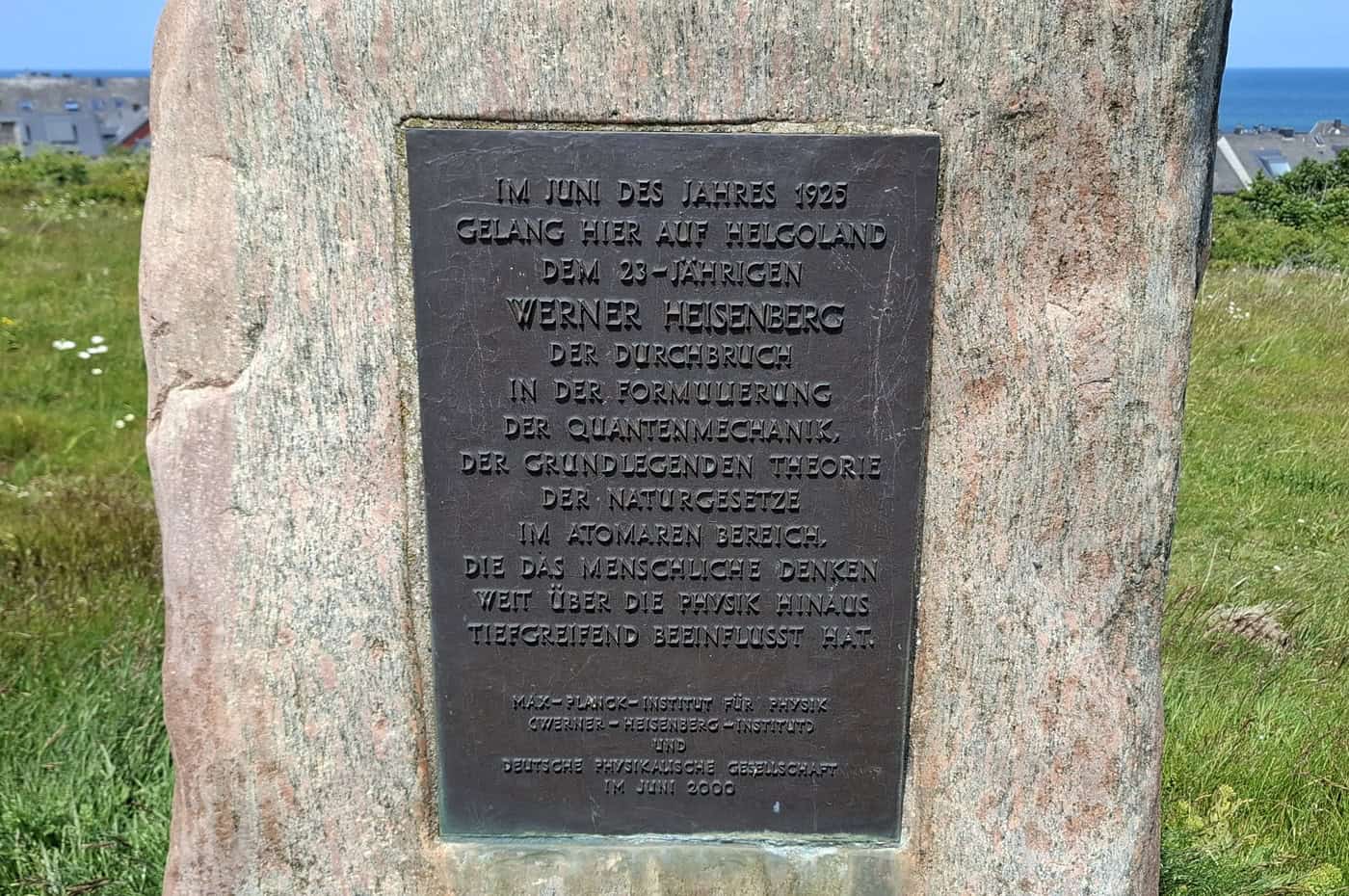

When Werner Heisenberg travelled to Helgoland in June 1925, he surely couldn’t have imagined that more than 300 researchers would make the same journey exactly a century later. But his development of the principles of quantum mechanics on the tiny North Sea island proved so significant that the crème de la crème of quantum physics, including four Nobel laureates, attended a five-day conference on Helgoland in June to mark the centenary of his breakthrough.

Just as Heisenberg had done, delegates travelled to the German archipelago by boat, leading one person to joke that if the ferry from Hamburg were to sink, “that’s basically quantum theory scuppered for a generation”. Fortunately, the vessel survived the four-hour trip up the river Elbe and 50 km out to sea – despite strong winds almost leading to a last-minute cancellation. The physicists returned in one piece too, meaning the future of quantum physics is safe.

These days Helgoland is a thriving tourist destination, offering beaches, bird-watching and boating, along with cafes, restaurants and shops selling luxury goods (the island benefits from being duty-free). But even 100 years ago it was a popular resort, especially for hay-fever sufferers like Heisenberg, who took a leave of absence from his post-doc under Max Born in Göttingen to seek refuge from a particularly bad bout of the illness on the windy and largely pollen-free island.

More than five years in the making, Helgoland 2025 was organized by Florian Marquardt and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light and Yale University quantum physicist Jack Harris, who said he was “very happy” with how the meeting turned out. As well as the quartet of Nobel laureates – Alain Aspect, Serge Haroche, David Wineland and Anton Zeilinger – there were many eager and enthusiastic early-career physicists who will be the future stars of quantum physics.

Questioning the foundations

When quantum physics began 100 years ago, only a handful of people were involved in the field. As well as Heisenberg and Born, there were the likes of Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac, Wolfgang Pauli, Niels Bohr and Pascual Jordan. If WhatsApp had existed back then, the protagonists would have fitted into their own small group chat (perhaps called “The Quantum Apprentices”). But these days quantum physics is a far bigger endeavour.

Helgoland 2025 covered everything from the fundamentals of quantum mechanics to applied topics such as sensors and quantum computing.

With 31 lectures, five panel debates and more than 100 posters, Helgoland 2025 had sessions covering everything from the fundamentals of quantum mechanics and quantum information to applied topics such as sensors and quantum computing. In fact, Harris said in an after-dinner speech on the conference’s opening night in Hamburg that he and the organizing team could easily have “filled two or three solid programmes with people from whom we would have loved to hear”.

Harris’s big idea was to bring together theorists working on the foundational aspects of quantum mechanics with researchers applying those principles to quantum computing, sensing and communications. “[I hoped they] would enjoy talking to each other on an equal footing,” he told me after the meeting. “These topics have a lot of overlap, but that overlap isn’t always well-represented at conferences devoted to one or the other.”

In terms of foundational questions, speakers covered issues such as entanglement, superposition, non-locality, the meaning of measurement and the nature of information, particles, quantum states and randomness. Nicholas Gisin from the University of Geneva said physics is, at heart, all about extracting information from nature. Renato Renner from ETH Zurich discussed how to treat observers in quantum physics. Zeilinger argued that quantum states are states of knowledge – but, if so, do they exist only when measured?

Italian theorist and author Carlo Rovelli, who was constantly surrounded in the coffee breaks, gave a lecture on loop quantum gravity as a solution to marrying quantum physics with general relativity. In a talk on quantizing space–time, Juan Maldacena from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton discussed information loss and black holes, saying that a “white” black hole the size of a bacterium would be as hot as the Sun and emit so much light we could see it with the naked eye.

Markus Aspelmeyer from the University of Vienna spoke about creating non-classical (i.e. quantum) sources of gravity in table-top experiments and tackled the prospect of gravitationally induced entanglement. Jun Ye from the University of Colorado, Boulder, talked about improving atomic clocks for fundamental physics. Bill Unruh from the University of British Columbia discussed the nature of particles, concluding that: “A particle is what a particle detector detects”.

It almost came as a relief when Gemma de les Coves from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona flashed up a slide joking : “I do not understand quantum mechanics.”

Applying quantum ideas

Discussing foundational topics might seem self-indulgent given the burgeoning (and financially lucrative) applications of quantum physics. But those basic questions are not only intriguing in their own right – they also help to attract newcomers into quantum physics. What’s more, practical matters like quantum computing, code breaking and signal detection are not just technical and engineering endeavours. “They hinge on our ability to understand those foundational questions,” says Harris.

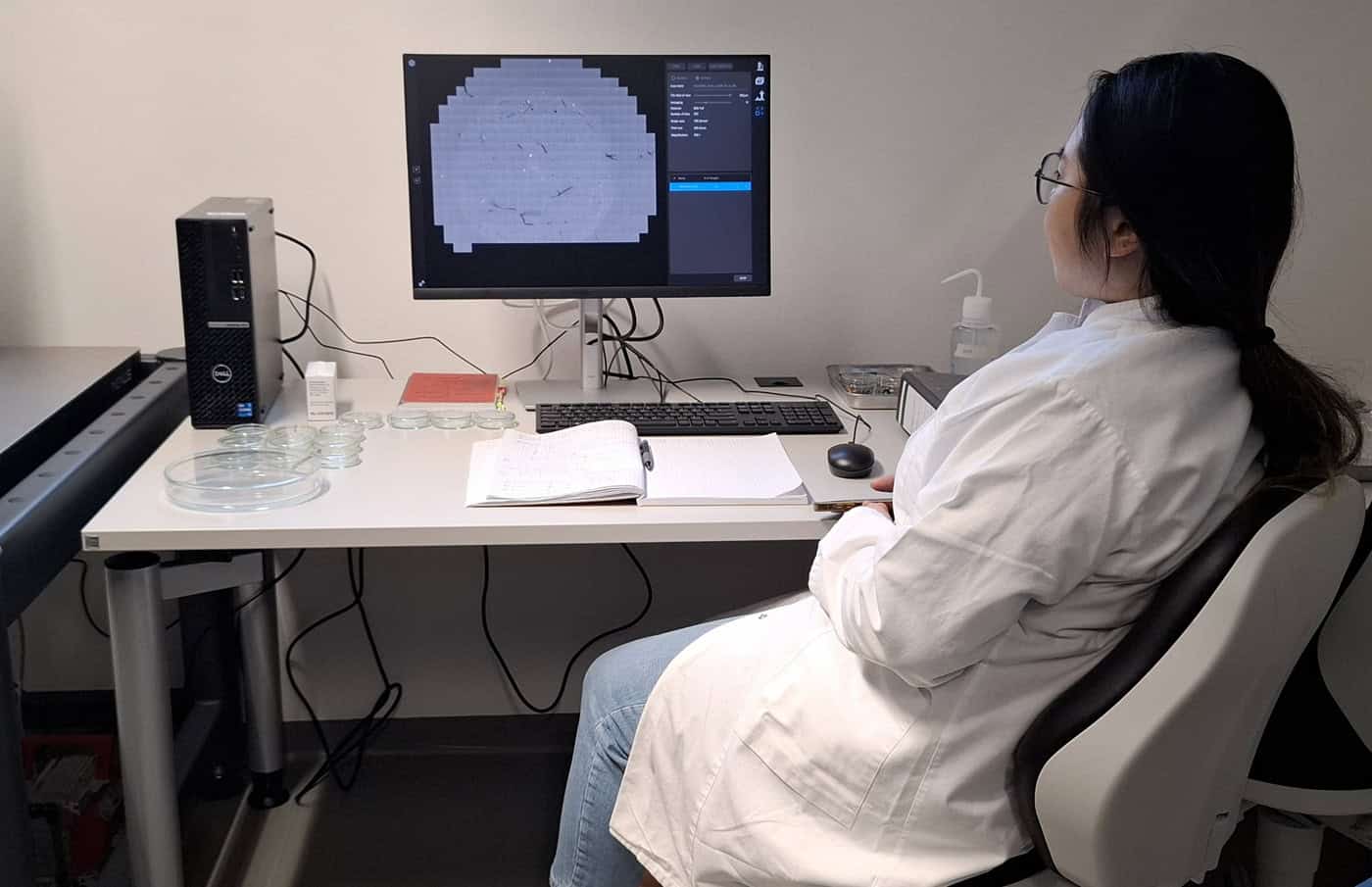

In fact, plenty of practical applications were discussed at Helgoland. As Michelle Simmons from the University of New South Wales pointed out, the last 25 years have been a “golden age” for experimental quantum physics. “We now have the tools that allow us to manipulate the world at the very smallest length scales,” she said on the Physics World Weekly podcast. “We’re able for the first time to try and control quantum states and see if we can use them for different types of information encoding or for sensing.”

One presenter discussing applications was Jian-Wei Pan from the University of Science and Technology of China, who spoke about quantum computing and quantum communication across space, which relies on sustaining quantum entanglement over long distances and times. David Moore from Yale discussed some amazing practical experiments his group is doing using levitated, trapped silica microspheres as quantum sensors to detect what he called the “invisible” universe – neutrinos and perhaps even dark matter.

Nergis Mavalvala from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, meanwhile, reminded us that gravitational-wave detectors, such as LIGO, rely on quantum physics to tackle the problem of “shot noise”, which otherwise limits their performance. Nathalie de Leon from Princeton University, who admitted on the final day she was going a bit “stir crazy” on the island, discussed quantum sensing with diamond.

Outside influences

Helgoland 2025 proved that quantum physicists have much to shout about, but also highlighted the many challenges still lying in store. How can we move from systems with just a few quantum bits to hundreds or thousands? How can quantum error correction help make noisy quantum systems reliable? What will we do with an exponential speed-up in computing? Is there a clear border between quantum and classical physics – and, if so, where is it?

By cooping participants together on an island with such strong historical associations, Harris hopes that Helgoland 2025 will have catalyzed new thinking. “I got to meet a lot of people I had always wanted to meet and re-connect with folks I’d been out of touch with for a long time,” he said. “I had wonderful conversations that I don’t think would have happened anywhere else. It is these kinds of person-to-person connections that often make the biggest impact.”

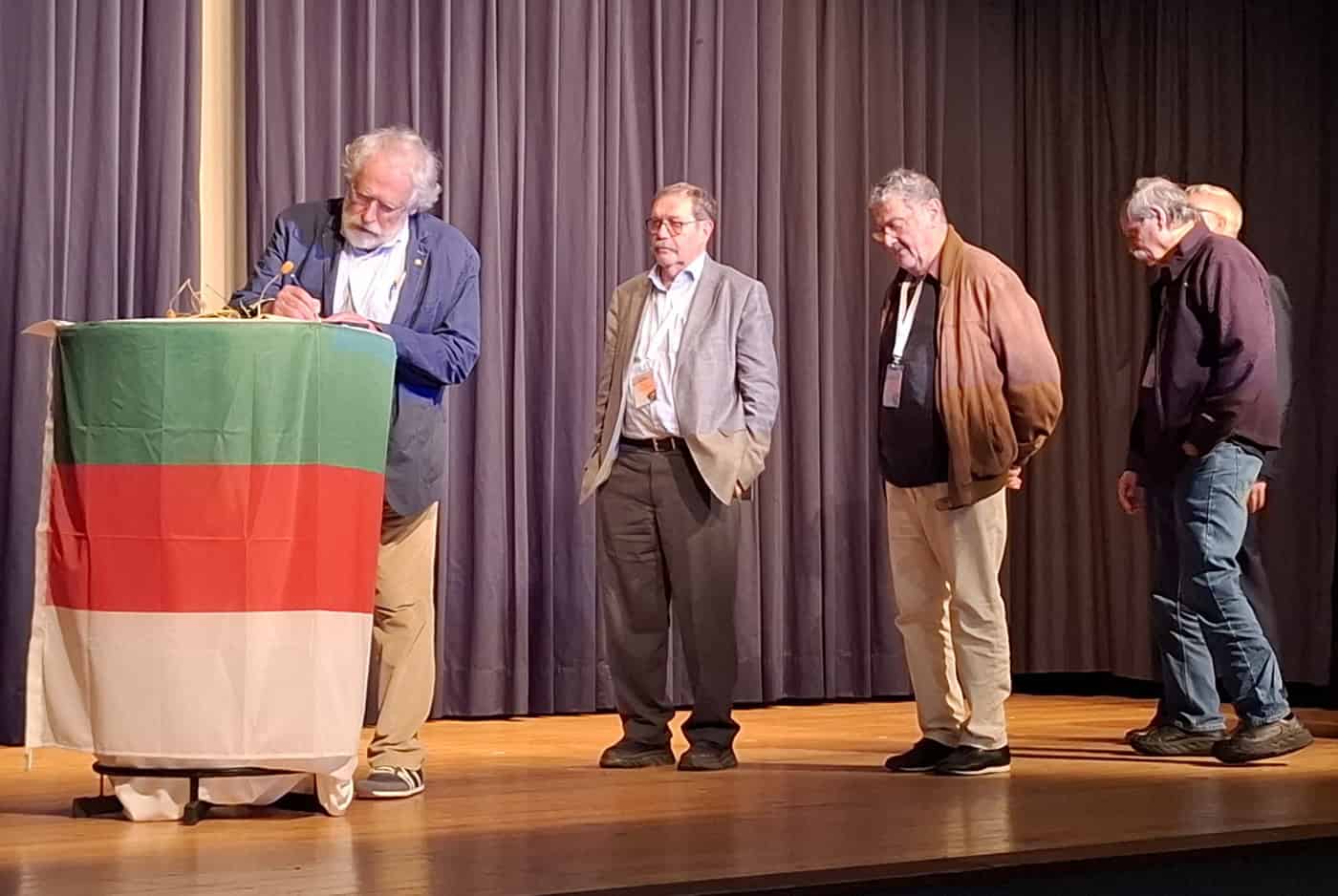

Occasionally, though, the outside world did encroach on the meeting. To a round of applause, Rovelli said that physicists must keep working with Russian scientists, and warned of the dangers of demonizing others. Pan, who had to give his talk on a pre-recorded video, said it was “with much regret” that he was prevented from travelling to Helgoland from China. There were a few rumbles about the conference being sponsored in part by the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Army Research Office.

Quantum physicists would also do well to find out more about the philosophy of science. Questions like the role of the observer, the nature of measurement, and the meaning of non-locality are central to quantum physics but are philosophical as much as scientific. Even knowing the philosophy relevant to the early years of quantum physics is important. As Elise Crull from the City University of New York said: “Physicists ignore this early philosophy at their peril”.

Towards the next century

The conference ended with a debate, chaired by Tracy Northup from the University of Innsbruck, on the next 100 years of quantum physics, where panellists agreed that the field’s ongoing mysteries are what will sustain it. “When we teach quantum mechanics, we should not be hiding the open problems, which are what interest students,” said Lorenzo Maccone from the University of Pavia in Italy. “They enjoy hearing there’s no consensus on, say the Wigner’s friend paradox. They seem engaged [and it shows] physics is not something dead.”

The importance of global links in science was underlined too. “Big advances usually come from international collaboration or friendly competition,” said panellist Gerd Leuchs from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light. “We should do everything we can to keep up collaboration. Scientists aren’t better people but they share a common language. Maintaining links across borders dampens violence.”

Leuchs also reminded the audience of the importance of scientists admitting they aren’t always right. “Scientists are often viewed as being arrogant, but we love to be proved wrong and we should teach people to enjoy being wrong,” he said. “If you want to be successful as a scientist, you have to be willing to change your mind. This is something that can be useful in the rest of society.”

I’ll leave the final word to Max Lock – a postdoc from the University of Vienna – who is part of a new generation of quantum physicists who have grown up with the weird but entirely self-consistent world of quantum physics. Reflecting on what happened at Helgoland, Lock said he was struck most by the contrast between what was being celebrated and the celebration itself.

“Heisenberg was an audacious 23-year-old whose insight spurred on a community of young and revolutionary thinkers,” he remarked. “With the utmost respect for the many years of experience and achievements that we saw on the stage, I’m quite sure that if there’s another revolution around the corner, it’ll come from the young members of the audience who are ready to turn the world upside down again.”

- Tracy Northup and Michelle Simmons appear alongside fellow quantum physicist Peter Zoller on the 19 June 2025 edition of the Physics World Weekly podcast

This article forms part of Physics World‘s contribution to the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), which aims to raise global awareness of quantum physics and its applications.

Stayed tuned to Physics World and our international partners throughout the year for more coverage of the IYQ.

Find out more on our quantum channel.

The post Helgoland 2025: the inside story of what happened on the ‘quantum island’ appeared first on Physics World.