Earth, air, fire, water: the growing links between climate change and geophysical hazards

A few years ago, Swiss seismologist Verena Simon noticed a striking shift in the pattern of seismic activity and micro earthquakes in the Mont Blanc region. She found that microquakes in the area, which straddles Switzerland, France and Italy, have fallen into an annual pattern since 2015.

Simon and colleagues at the Swiss Seismological Service in fact found that this annual pattern is linked to heat waves driven by climate change. But they are not the only researchers finding such geophysical links to climate change. There is growing evidence that global warming could cause changes in seismicity, volcanic activity and other such hazards.

In the first eight years from 2006, Simon’s team saw no clear pattern. But then from 2015 they found that seismicity always increases in autumn and stays at a higher level until winter. The researchers wondered if the seasonal pattern was linked to a known increase in meltwater infiltration into the Mont Blanc massif in late summer and autumn every year.

Seasonal seismic trends

Scientists have long known that when water percolates underground it increases the pressure in gaps, or pores, in rocks, which alters the balance of forces on faults, leading to slips – and triggering seismic activity.

In the late 1990s researchers analysed water flow into the 12 km long Mont Blanc tunnel, which links France and Italy (La Houille Blanche 86 78). They also found a yearly pattern, with a rapid increase in water entering the tunnel between August and October. The low mineral content of the water and results from tracer tests, using fluorescent dyes injected into a glacier crevasse on the massif, confirmed that this increased flow was fresh water from snow and glacier melt.

To explore the seasonal trend in the water table, Simon and colleagues created a hydrological model (a simplified mathematical model of a real-world water flow system) using the tunnel inflow data; plus metrological, hydrological and snow-pack data from elsewhere in the Alps. They also included information on how water diffuses into rocks, alters pore pressure and increases seismic activity (Earth and Planetary Sci. Lett. 666 119372).

When combined with their seismicity data, autumn seismic activity appeared to be triggered by spring surface runoff, which arises from melting glacial ice and snow. The exact timing depends on the depth of the microquakes, with shallow quakes being linked to surface runoff from the previous year, while there is a two-year delay between runoff and deeper quakes. Essentially, their work found a link between meltwater and seismic activity in the Mont Blanc massif; but it could not explain why the autumn increase in microquakes only started in 2015.

Perhaps the answer lies in historic meteorological data of the area. In 2015 the Alps experienced a prolonged, record-breaking heatwave, which led to very many high-altitude rockfalls in a number of areas, including in the Mont Blanc massif, as rock-wall permafrost warmed. Data also show that since then there has been a big increase in days when the average temperatures in the Swiss Alps is above 0 °C. These so-called “positive degree days” are known to lead to increased glacial melt.

All of these findings support the idea that the onset of seasonal seismic activity is linked to climate change-induced increases in meltwater and alterations in flow paths. Simon explains that rock collapses can alter the pathways that water follows as it infiltrates into the ground. Combined with increases in meltwater, this can lead to pore-pressure changes that increase seismicity and trigger it in new places.

These small earthquakes in the Mont Blanc massif are unlikely to trouble local communities. But the researchers did find that at times the seismic hazard – an indicator of how often and intensely the earth could shake in a specific area – rose by nearly four orders of magnitude, compared with pre-2015 level. They warn that similar processes in glaciated areas that experience larger earthquakes than the Alps, such as the Himalayas, might be less gentle.

Extreme rainfall

Climate change is also altering water-flow patterns by increasing the intensity of extreme weather events and heavy rainfall. And there is already evidence that such extreme precipitation can influence seismic activity.

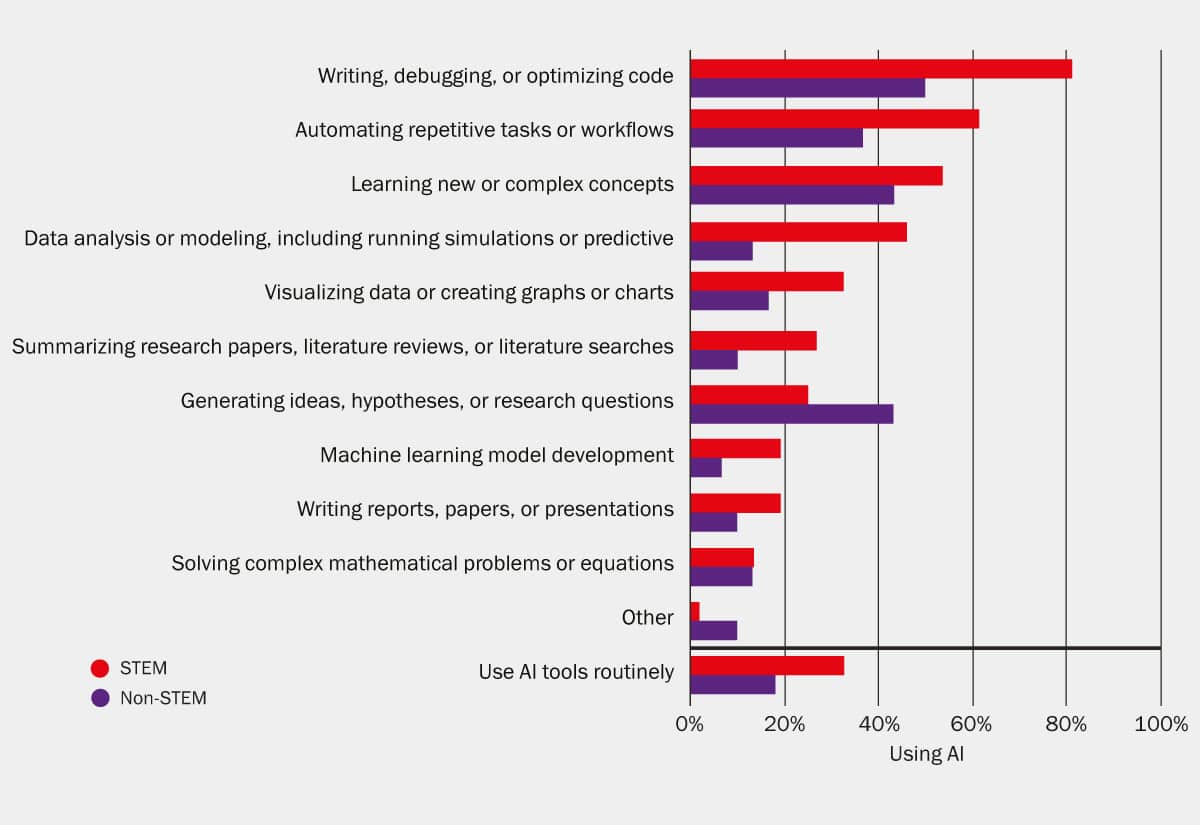

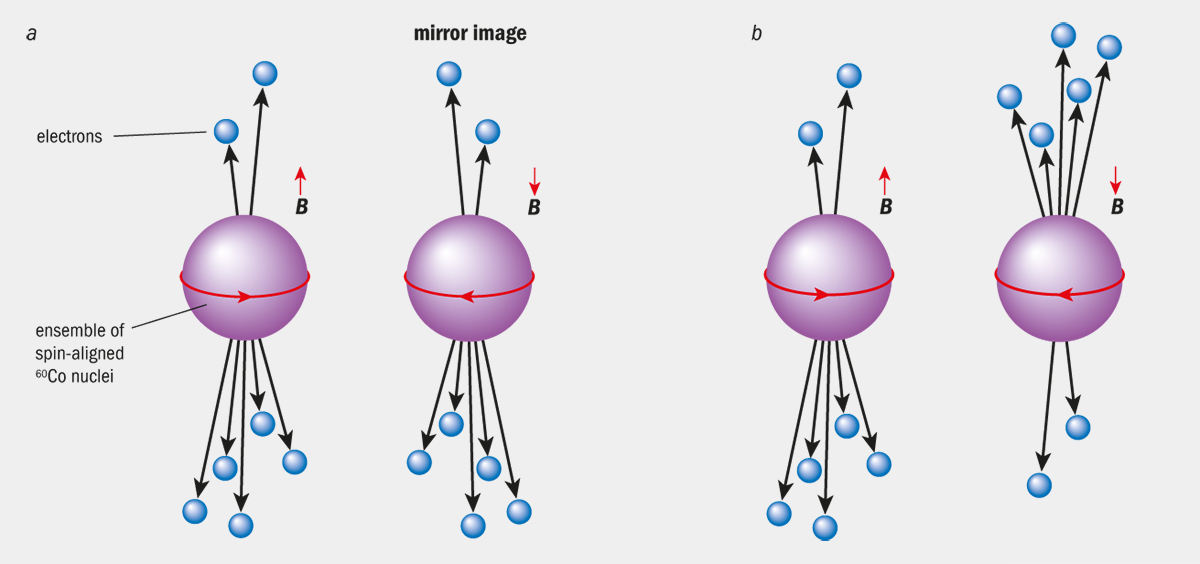

In 2020 Storm Alex brought record-breaking rainfall to the south-east of France, with some areas seeing more than 600 mm in 24 hours. In the following 100 days 188 earthquakes were recorded in the Tinée valley, in south-eastern France. Although all were below two in magnitude, that volume of microquakes would usually be spread over a five-year period in the region. A 2024 analysis carried out by seismologists in France concluded that increased fluid pressure from the extreme rainfall caused a stressed fault system to slip, initiating a seismic swarm – a localized cluster of earthquakes, without a single “mainshock”, that take place over a relatively short period of days, months or years (see figure 1).

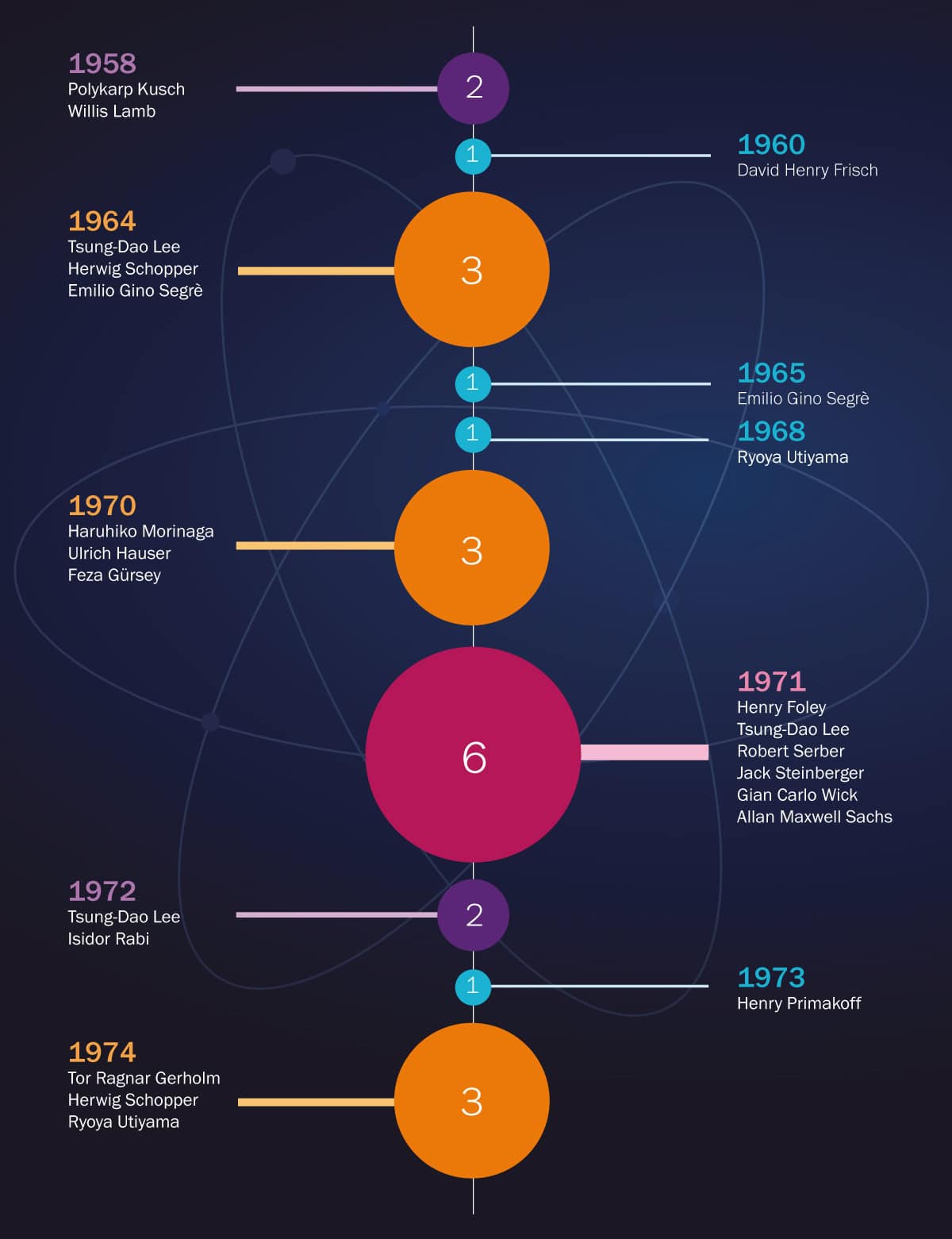

1 How extreme rainfall triggers seismic swarms

French seismologist Laeticia Jacquemond and colleagues have developed a model showing the sequence of mechanisms that likely trigger a seismic swarm, which is a localized cluster of earthquakes. The sequence starts with abrupt and extreme rainfall, like 2020’s Storm Alex. Thanks to open fault zones, a lot of rainfall is transmitted deep within a critically stressed crust. The fluid invasion through the fractured medium then induces a poroelastic response of the crust at shallow depths, triggering or accelerating a seismic slip on fault planes. As this slip propagates through the fault network, it pressurizes and stresses locked asperities (areas on an active fault where there is increased friction), predisposed to rupture, and initiates a seismic swarm.

There have been other examples in Europe of seismic activity linked to extreme rainfall. For instance, in September 2002 a catastrophic storm in western Provence in southern France, with similar rainfall levels as Storm Alex, triggered a clear and sudden increase in seismic activity, a study concluded. While another analysis found that an unusual series of 47 earthquakes over 12 hours in central Switzerland in August 2005 was likely caused by three days of intense rainfall.

According to Marco Bohnhoff from the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany, the link between fluid infiltration into the ground and seismicity is well understood – from fluid injection for oil and gas production, to geothermal development and heavy rainfall. “The pore pressure is increased if there is a small load on top, enforced by water, and that changes the pressure conditions in the underground, which can release energy that is already stored there,” Bohnhoff explains.

A good example of this is the Koyna Dam, one of India’s largest hydroelectric projects, which consists of four dams. Every year during the monsoon season the water level in the reservoir behind the dams increases by about 20–25 m, and with this comes an increase in seismic activity. “After the rain stops and the water level decreases, the earthquake activity stops,” says Bohnhoff. “So, the earthquake activity distribution nicely follows the water level.”

Rising seas and seismic activity

According to Bohnoff, anything that increases the pressure underground could trigger earthquakes. But he has also been studying the effect of another consequence of climate change: sea-level rise.

Undisputed and accelerating, sea-level rise is driven by two main effects linked to climate change: the expansion of ocean waters as they warm, and the melting of land ice, mainly the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. According to the World Meteorological Organization, sea levels will rise by half a metre by 2100 if emissions follow the Paris Agreement, but increases of up to two metres cannot be ruled out if emissions are even higher.

As ocean waters increase, so does the load on the underground. “This will change the global earthquake activity rate,” says Bohnhoff. In a study published in 2024, Bohnhoff and colleagues found that sea-level rise will advance the seismic clock, leading to more and in some cases stronger earthquakes (Seismological Research Letters 95 2571).

“It doesn’t mean that all of a sudden there will be earthquakes everywhere, but earthquakes that would have occurred sometime in the future will occur sooner,” he says. “We’re changing the regularity of earthquakes.” The risk created by this is greatest in coastal mega-cities, located near critical fault zones, such as San Francisco and Los Angeles in the US; Istanbul in Turkey; and Tokyo and Yokohama in Japan.

The findings cannot be used to predict individual earthquakes – in fact, it is very difficult to predict how much the seismic clock will advance, as it depends on the amount of sea-level rise. But there are faults around the world that are critically stressed and close to the end of their seismic cycle.

“Faults that are very, very close to failure, where basically there would be an earthquake, say in 100 years or 50 years, they might be advanced and that might occur very soon,” he explains.

Between a rock and a hard place

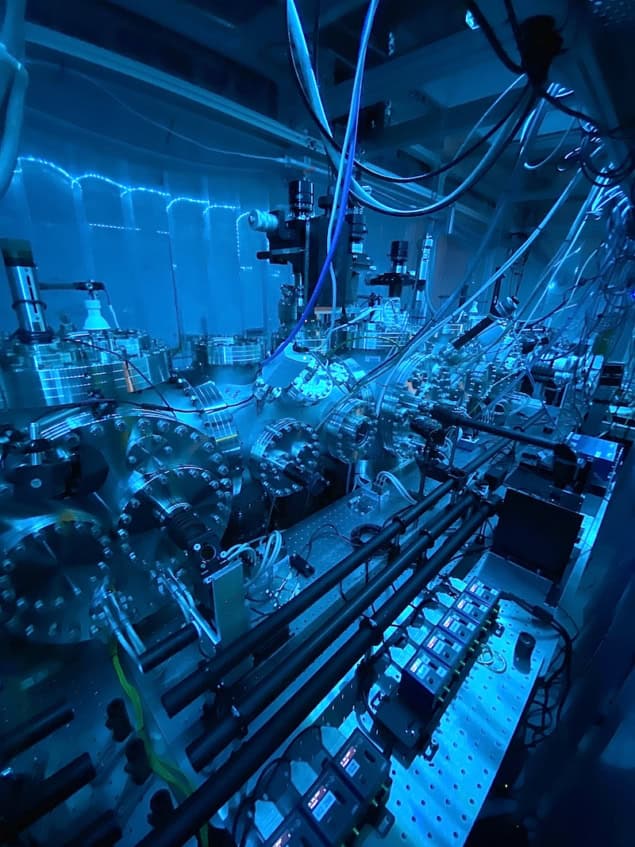

Another significant geological hazard linked to climate change and heavy rainfall is volcanic activity. In December 2021 there was devastating eruption of Mount Semeru, on the Indonesian island of Java. “There was a really heavy rainfall event and that caused the collapse of the lava dome at the summit,” says Jamie Farquharson, a volcanologist at Niigata University in Japan.

This led to a series of eruptions, pyroclastic flows and “lahars” – devastating flows of mud and volcanic debris – that killed at least 69 people and damaged more than 5000 homes. Although it is challenging to attribute this specific event to climate change, Farquharson says that it is a good example of how global warming-induced heavy rainfall could exacerbate volcanic hazards.

Farquharson and colleagues noticed links between ground deformations and rainfall at several volcanoes. “We started seeing some correlations and thought why shouldn’t we? Because from a rock mechanics point of view, these volcanoes would be more prone to fracturing and other kinds of failure when the pore pressure is high,” says Farquharson. “And one of the easiest ways of increasing pore pressure is by dumping a load of rain onto the volcano.”

Such rock fracturing can open new pathways for magma to propagate towards the surface. This can happen deep underground, but also near the surface, for instance by causing a chunk of the flank to slide off a volcano. As with earthquakes, these changes could alter the timing of eruptions. For volcanoes that might be primed for an eruption, where the magma chamber is inflating, extreme rainfall events might hasten an eruption. But as Farquharson explains, such rainfall events “could bring something that was going to happen at an unspecified point in the future across a tipping point”.

A few years ago Farquharson, together with atmospheric scientist Falk Amelung of the University of Miami in the US, published a study showing that if global warming continues at current rates, rainfall-linked volcanic activity – such as dome explosions and flank collapses – will increase at more than 700 volcanoes around the globe (R. Soc. Open Sci. 9 220275).

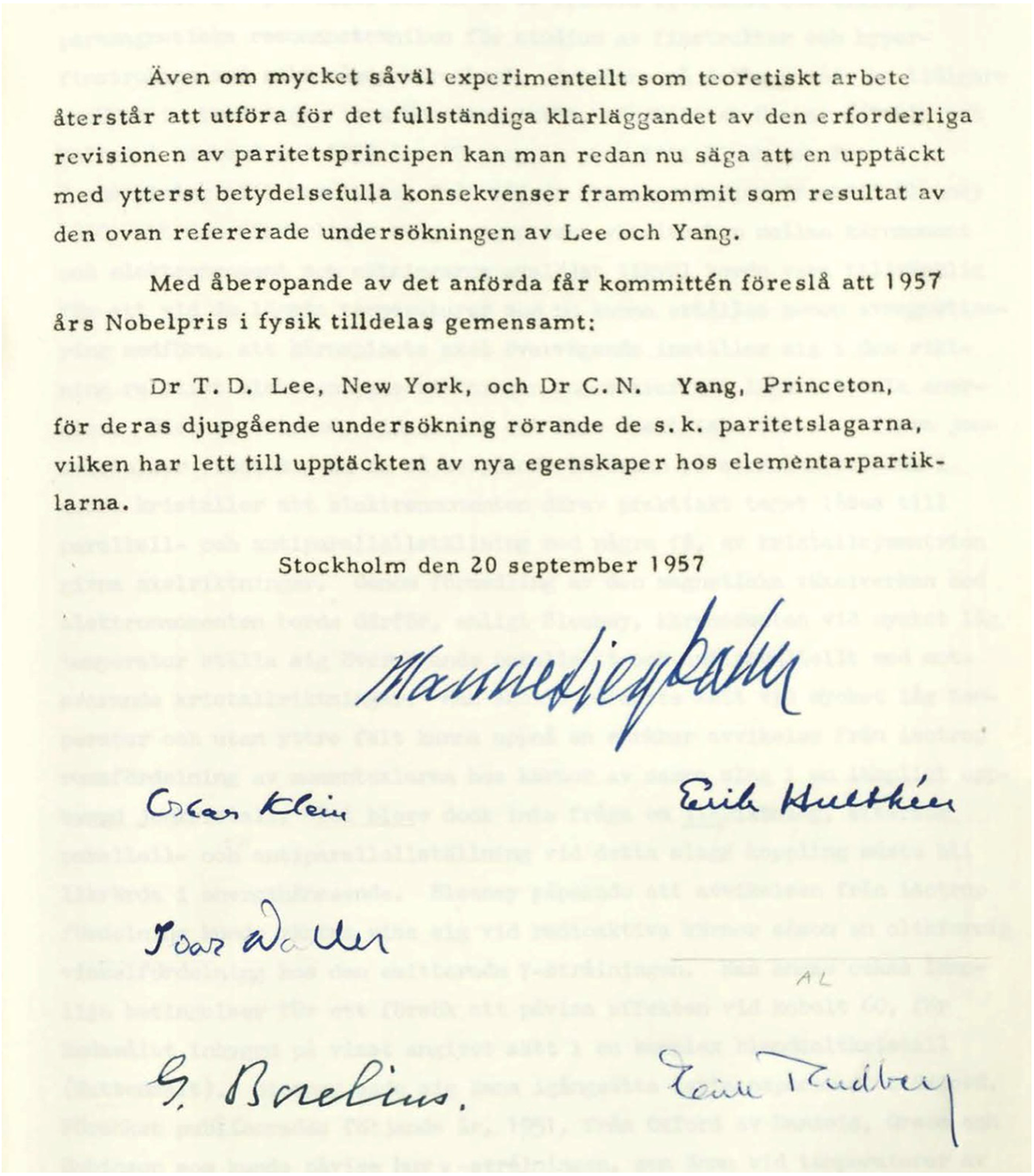

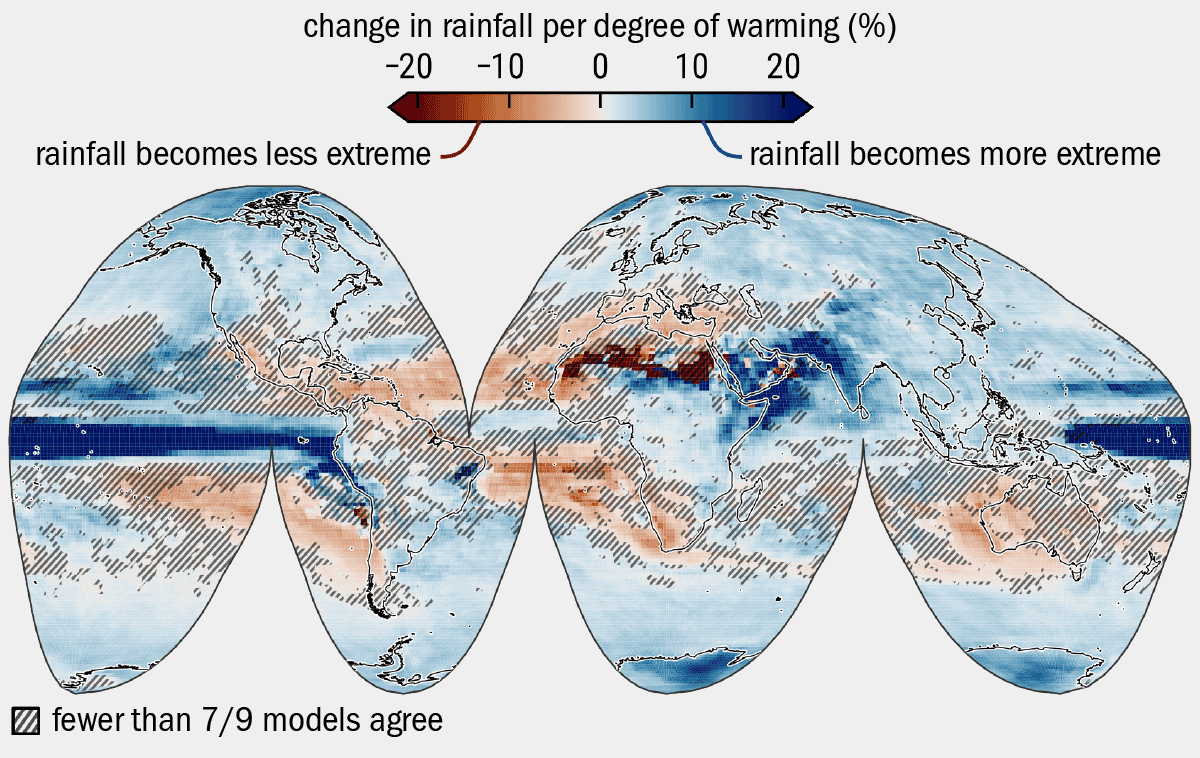

To explore the impact of rainfall, Farquharson and Amelung analysed decades of reports on volcanic activity from the Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism Program. This showed that heavy or extreme rainfall has been linked to eruptions and other hazards, such as lahars at at least 174 volcanoes (see figure 2).

There are 1234 volcanoes on land that have been active in the Holocene, the current geological epoch, which began around 12,000 years ago. The geologists used nine different models to explore how climate change might alter rainfall at these volcanos. They found that 716 of these volcanoes will experience more extreme rainfall as global temperatures continue to rise. The models did not agree on whether rainfall will become more or less extreme at 407 of the volcanoes, and the remaining 111 are in regions expected to see a drop in heavy rain.

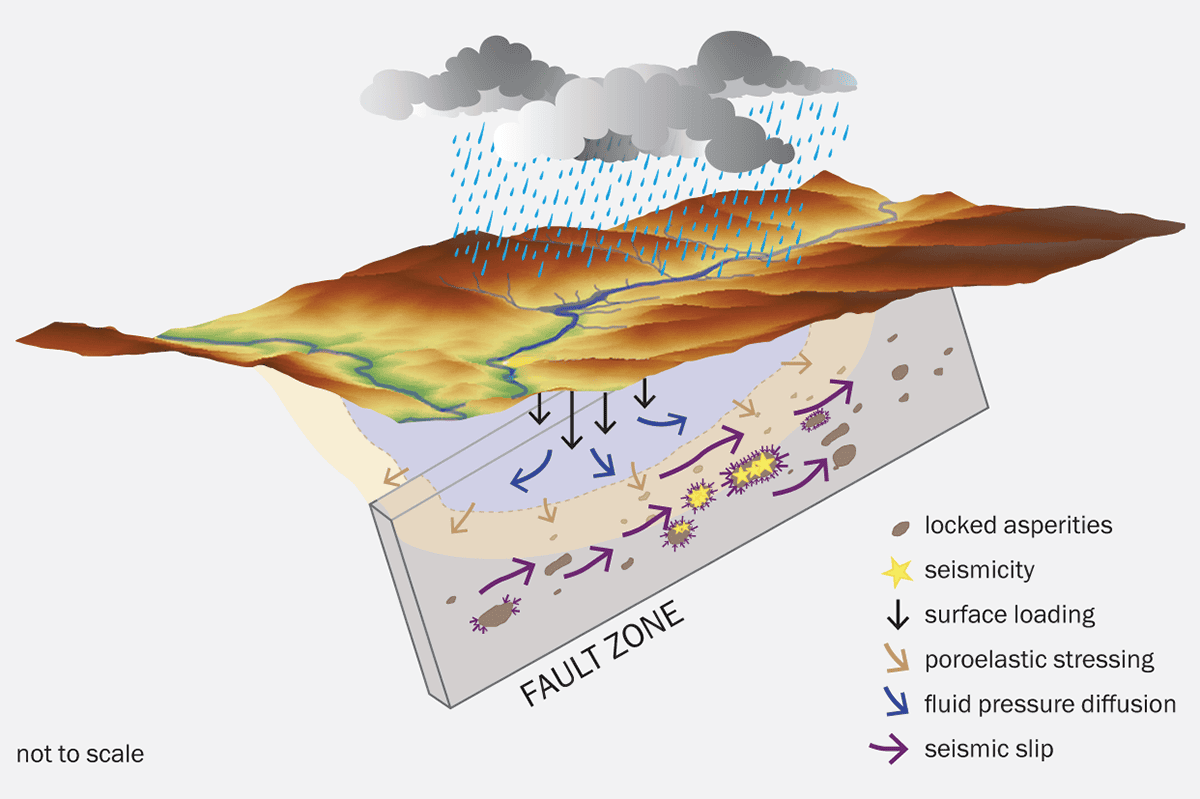

2 Modelling magma

Jamie Farquharson and colleagues are studying how heavy rainfall drives a range of volcanic hazards. The colours on the map reflect the “forced model response” (FMR) – the percentage change of heavy precipitation for a given unit of global warming. Serving as a proxy for the likelihood of extreme rainfall events, the value of FMR was averaged from nine different “general circulation models” (i.e. global climate models). FMR is shown here as the percentage rise or fall in extreme rainfall projected by the models for every degree of global warming between 2005 and 2100 CE. The darkest reds show areas that will experience a 20% or more decrease in extreme rainfall for each degree of warming, while the darkest blues highlight areas which will experience a 20% or more increase in extreme rainfall per degree of warming. The figures were made with CMIP5 model data, which assumes a “high emissions” scenario. Their results suggest that if global warming continues unchecked, the incidence of primary and secondary rainfall-related volcanic activity – such as dome explosions or flank collapse – will increase at more than 700 volcanoes around the globe.

Volcanic regions where heavy rainfall is expected to increase include the Caribbean islands, parts of the Mediterranean, the East African Rift system, and most of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

In fact, volcanic hazards in many of these regions have already been linked to heavy rainfall. For instance, in 1998 extreme rainfall in Italy led to devastating debris flows on Mount Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei, near Naples, killing 160 people.

Elsewhere, rainfall has sparked explosive activity at Mount St Helens, in the Cascade Mountains of Canada and the western US. Other volcanoes in this range, which is part of the Ring of Fire, put major population centres at significant lahar risk, due to their steep slopes. In both the Caribbean and Indonesia – the world’s most volcanically active country, heavy rainfall has triggered explosive activity and eruptions at active volcanoes.

Farquharson and Amelung warn that if heavy rainfall increases in these regions as predicted, it will heighten an already considerable threat to life, property and infrastructure. As we enter a new era of much higher resolution climate modelling, Farquharson hopes that we will “be able to get a much better handle on exactly which [volcanic] systems could be affected the most”. This may enable scientists to better estimate how hazards will change at specific geographical locations.

Fire and ice

Scientists are also concerned about what will happen to volcanoes currently buried under ice as the climate warms. Through modelling work and studying volcanoes that sat below the Patagonian Ice Sheet during and at the end of the last ice age, Brad Singer, a geoscientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the US, and colleagues have been exploring the impact of deglaciation on volcanic processes.

They found that ice loss can lead to an increase in large explosive eruptions. This occurs because as the ice melts, the weight on the volcano drops, which allows magma to expand and put pressure on the rock within the volcano. Also, as pressure from the ice reduces, dissolved volatile gases like water and carbon dioxide separate from the magma to form gas bubbles. This further increases the pressure in the magma chamber, which can promote an eruption.

But each volcano responds differently to ice. Singer’s team has been dating and studying the chemical composition of lava flow samples from South America, to track the behaviour of volcanoes over tens of thousands of years, through the build-up of the ice and after deglaciation.

The Patagonian Ice Sheet began to melt very rapidly about 18,000 years ago and by about 16,000 years ago it was gone. “We develop a timeline and put compositions on that timeline and look to see if there were any changes in the composition of the magmas that were erupting as a function of the thickness of the ice sheet,” explains Singer. “We are finding some really interesting things.”

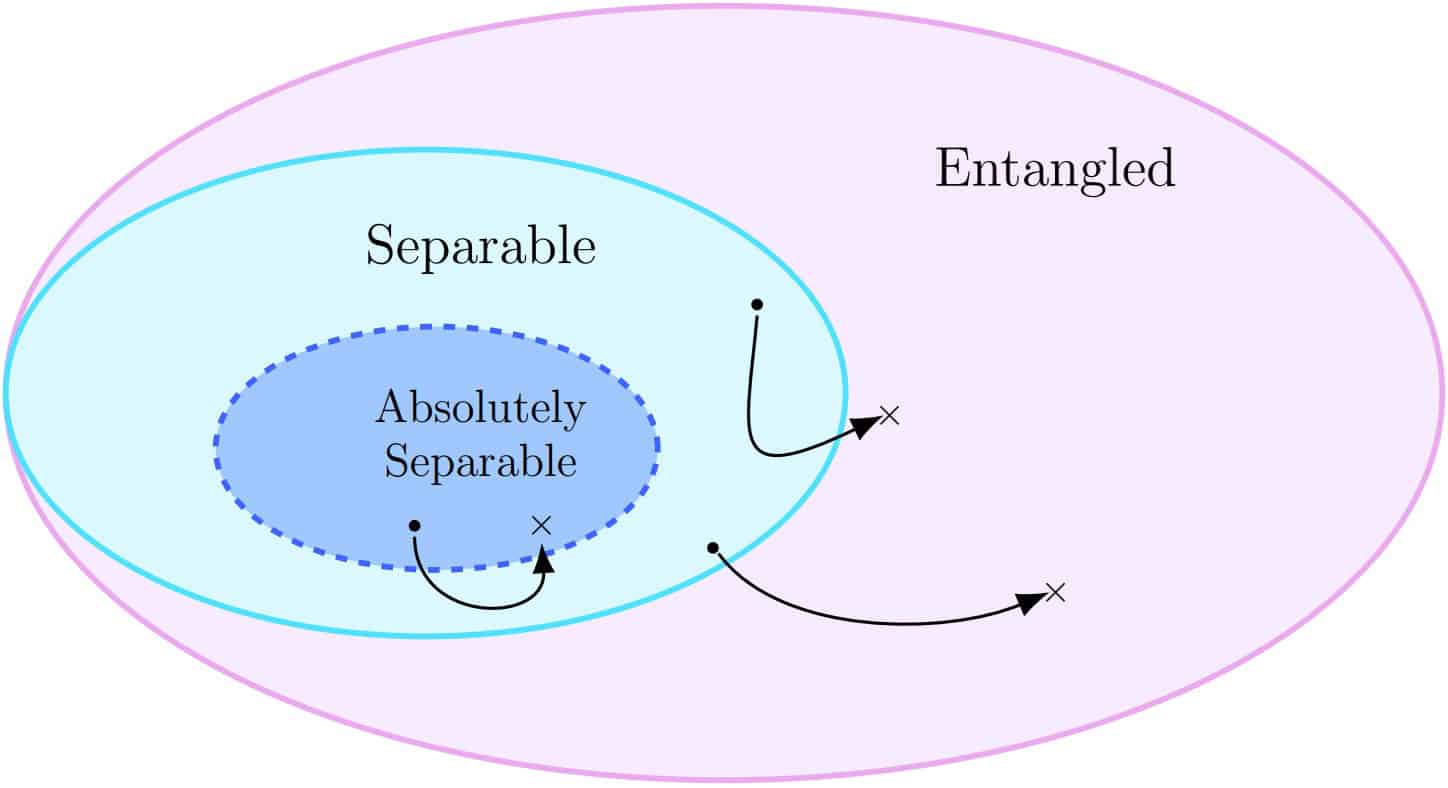

The Puyehue-Cordón Caulle and Mocho-Choshuenco volcanic complexes in southern Chile both erupt rhyolitic magmas. But they were not producing this type of magma before the ice retreated, as Singer and colleagues found (GSA Bulletin 136 5262) (see figure 3).

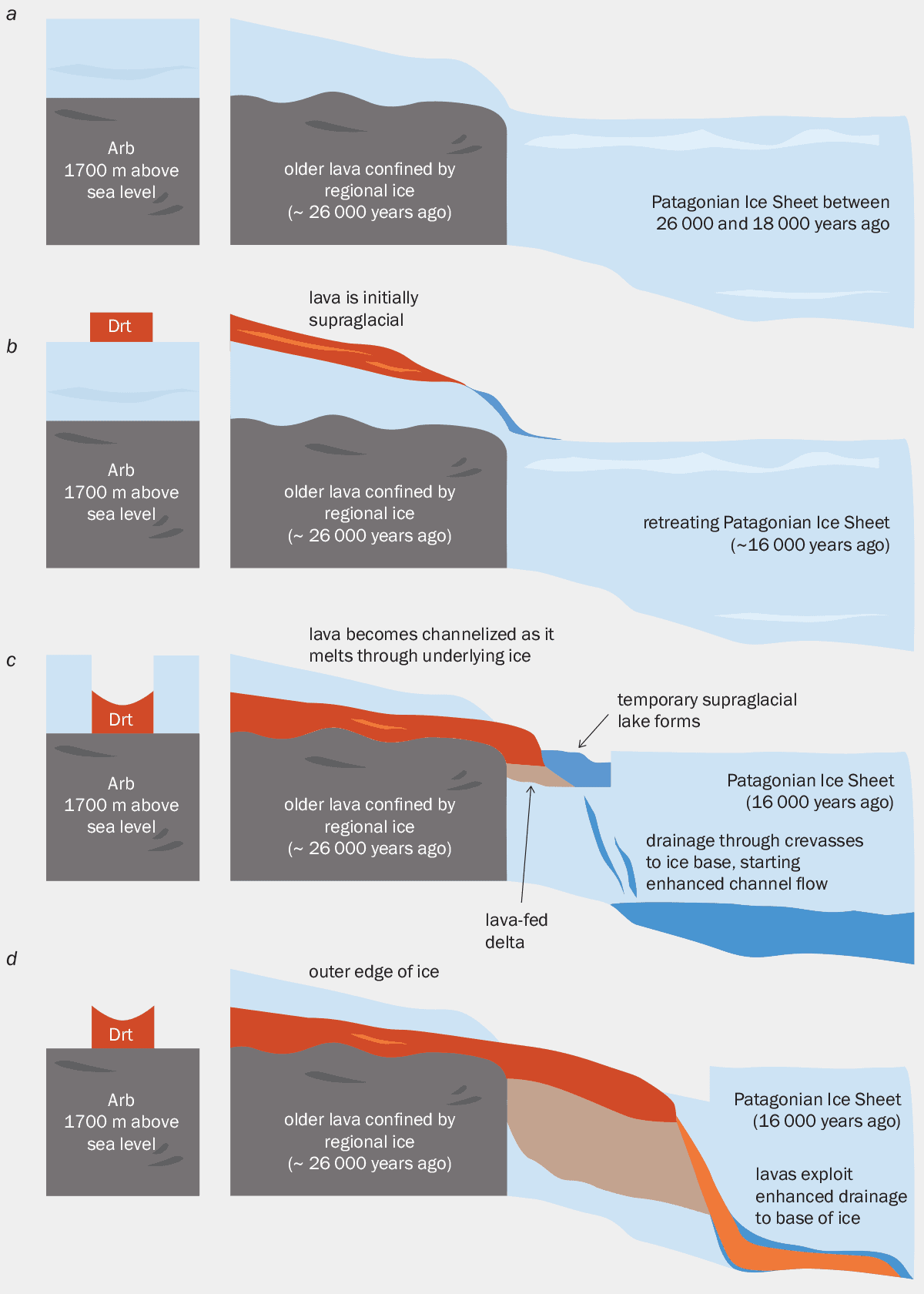

3 When volcanic lava and ice interact

Geologist Brad Singer and colleagues are studying how glaciers and ice sheets impact the evolution of volcanoes, to develop a “lava-fed delta” model. (a) The researchers studied basaltic andesites in the Río Blanco river in Argentina (Arb). A fine-grained extrusive igneous rock that forms when volcanic magma erupts and crystallizes outside of the volcano, basaltic andesites were impounded by the Patagonian Ice Sheet roughly 26,000 years ago. Here they formed cliffs that were then occupied by the Patagonian Ice Sheet at 1500–1700 m above sea level between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago. Ice on top of the edifice should have been comparatively thinner than in the surrounding valleys. (b) As the ice sheet retreated between 18,000 and 16,000 years ago, dacite – a fine-grained volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides – from the Río Truful river in Chile (Drt) flowed onto it. (c) Lava is channelized as it melts the ice to form a lava-fed delta. (d) Dacite flows through the ice and to its base.

“We don’t know for sure that [magma change] is attributable to the glaciation, but it is curious that immediately following the deglaciation we start to see the first appearance of these highly explosive rhyolitic magmas,” says Singer. The volcanologists suspect that the ice sheet reduced eruptions at these volcanos, leading magma to accumulate over thousands of years. “That accumulated reservoir can evolve into this explosive dangerous magma type called rhyolite,” Singer adds.

But that didn’t always happen. The Calbuco volcano, in southern Chile, has always erupted andesite, an intermediate-composition magma. “It’s never erupted basalt, it’s never erupted rhyolite, it’s erupting andesite, regardless of whether the ice is there or not,” explains Singer.

There are also differences in how quickly volcanoes reacted to the deglaciation. At Mocho-Choshuenco, for example, there was a large rhyolite eruption about 3000 years after the loss of ice. Singer suspects that the delay “reflects the time that it took to exsolve the volatiles from the rhyolite”. But at the nearby, very active Villarrica volcano, there was no such delay. It experienced a huge eruption 16,800 years ago, almost immediately after the ice disappeared.

Melting ice sheets

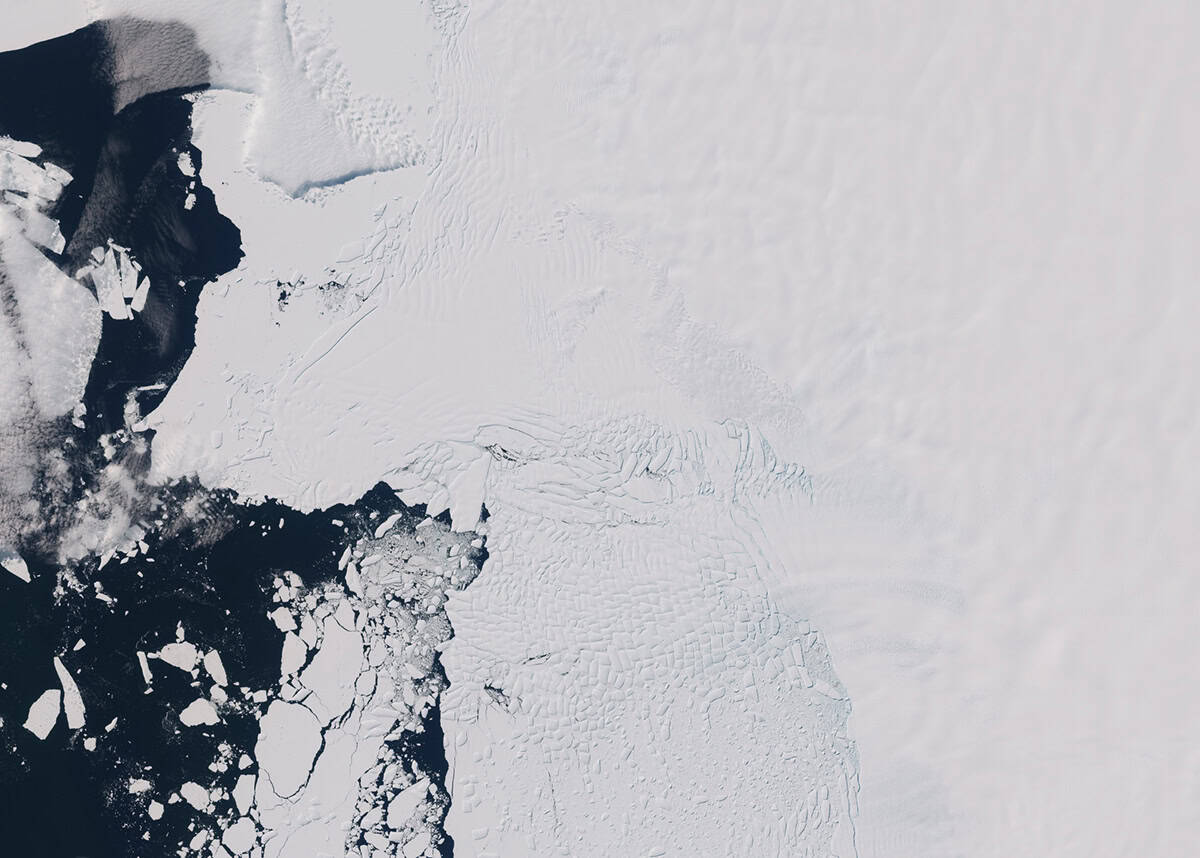

Volcanic activity from melting ice sheets, due to current climate change, is probably not a direct hazard to people. But below the West Antarctic Ice Sheet sits the West Antarctic Rift – a system that is thought to contain at least 100 active volcanoes.

A major contributor to global sea-level rise, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is particularly vulnerable to collapse as temperatures rise. If they become more active and explosive, the volcanoes of the West Antarctic Rift System could accelerate ice melting and sea-level rise.

“The melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could remove the surface load that’s preventing eruptions from occurring,” says Singer. Such eruptions could bring lava and heat to the base of the ice sheet, which is dangerous because melting at the base can cause the ice to move faster into the ocean. The resulting rising sea levels could go on to advance the seismic clock and trigger earthquakes.

In the long run, increased volcanic activity will impact global climate, with the cumulative effect of multiple eruptions contributing to global warming thanks to a build-up of greenhouse gases. Essentially, a positive feedback loop is created, as melting ice caps, helped by volcanoes, could lead to more earthquakes. Managing the Earth’s warming and protecting the world’s remaining glaciers and ice sheets is therefore more crucial than ever.

The post Earth, air, fire, water: the growing links between climate change and geophysical hazards appeared first on Physics World.