Metallic material breaks 100-year thermal conductivity record

A newly identified metallic material that conducts heat nearly three times better than copper could redefine thermal management in electronics. The material, which is known as theta-phase tantalum nitride (θ-TaN), has a thermal conductivity comparable to low-grade diamond, and its discoverers at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), US say it breaks a record on heat transport in metals that had held for more than 100 years.

Semiconductors and insulators mainly carry heat via vibrations, or phonons, in their crystalline lattices. A notable example is boron arsenide, a semiconductor that the UCLA researchers previously identified as also having a high thermal conductivity. Conventional metals, in contrast, mainly transport heat via the flow of electrons, which are strongly scattered by lattice vibrations.

Heat transport in θ-TaN combines aspects of both mechanisms. Although the material retains a metal-like electronic structure, study leader Yongjie Hu explains that its heat transport is phonon-dominated. Hu and his UCLA colleagues attribute this behaviour to the material’s unusual crystal structure, which features tantalum atoms interspersed with nitrogen atoms in a hexagonal pattern. Such an arrangement suppresses both electron–phonon and phonon–phonon scattering, they say.

Century-old upper limit for metallic heat transport

Materials with high thermal conductivity are vital in electronic devices because they remove excess heat that would otherwise impair the devices’ performance. Among metals, copper has long been the material of choice for thermal management thanks to its relative abundance and its thermal conductivity of around 400 Wm−1 K−1, which is higher than any other pure metal apart from silver.

Recent theoretical studies, however, had suggested that some metallic-like materials could break this record. θ-TaN, a metastable transition metal nitride, was among the most promising contenders, but it proved hard to study because high-quality samples were previously unavailable.

Highest thermal conductivity reported for a metallic material to date

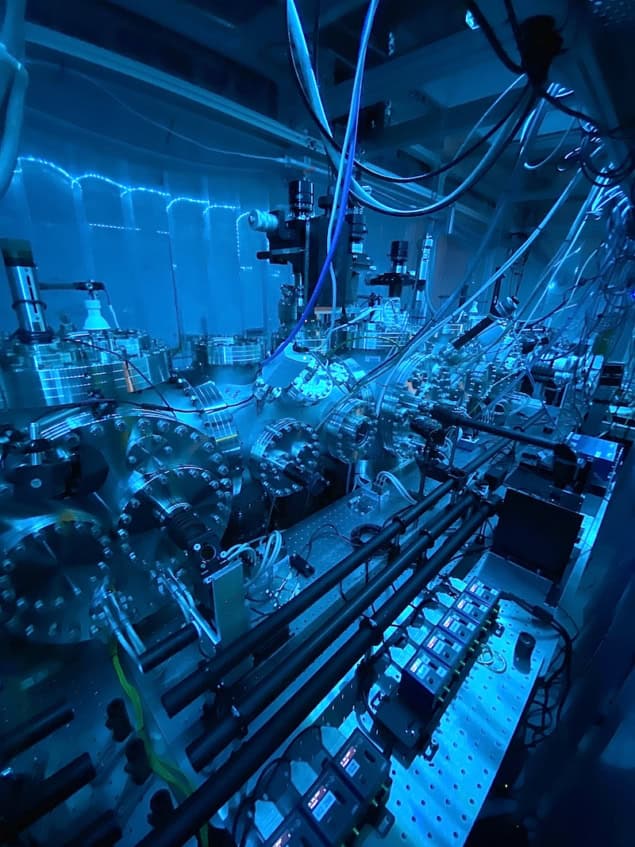

Hu and colleagues overcame this problem using a flux-assisted metathesis reaction. This technique removed the need for the high pressures and temperatures required to make pure samples of the material using conventional techniques.

The team’s high-resolution structural measurements revealed that the as-synthesized θ-TaN crystals had smooth, clean surfaces and ranged in size from 10 to 100 μm. The researchers also used a variety of techniques, including electron diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, single-crystal X-ray diffraction, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy and electron energy loss spectroscopy to confirm that the samples contained single crystals.

The researchers then turned their attention to measuring the thermal conductivity of the θ-TaN crystals. They did this using an ultrafast optical pump-probe technique based on time-domain thermoreflectance, a standard approach that had already been used to measure the thermal conductivity of high-thermal-conductivity materials such as diamond, boron phosphide, boron nitride and metals.

Hu and colleagues made their measurements at temperatures between 150 and 600 K. At room temperature, the thermal conductivity of the θ-TaN crystals was 1100 Wm−1 K−1. “This represents the highest value reported for any metallic materials to date,” Hu says.

The researchers also found that the thermal conductivity remained uniformly high across an entire crystal. H says this reflects the samples’ high crystallinity, and it also confirms that the measured ultrahigh thermal conductivity originates from intrinsic lattice behaviour, in agreement with first-principles predictions.

Another interesting finding is that while θ-TaN has a metallic electronic structure, its thermal conductivity decreased with increasing temperature. This behaviour contrasts with the weak temperature dependence typically observed in conventional metals, in which heat transport is dominated by electrons and is limited by electron-phonon interactions.

Applications in technologies limited by heat

As well as cooling microelectronics, the researchers say the discovery could have applications in other technologies that are increasingly limited by heat. These include AI data centres, aerospace systems and emerging quantum platforms.

The UCLA team, which reports its work in Science, now plans to explore scalable ways of integrating θ-TaN into device-relevant platforms, including thin films and interfaces for microelectronics. They also aim to identify other candidate materials with lattice and electronic dynamics that could allow for similarly efficient heat transport.

The post Metallic material breaks 100-year thermal conductivity record appeared first on Physics World.