Vue lecture

Trump backs off Greenland tariffs, citing ‘framework’ deal after meeting with NATO official

Todd Blanche warns Americans 'should be worried' about Minnesota protests after church disruption

Le Bayern qualifié pour les huitièmes, Chelsea met la pression sur le PSG, Khephren Thuram libère la Juventus

Grâce à Harry Kane, le Bayern Munich a assuré sa place dans le top 8 après sa victoire face l'Union Saint-Gilloise (2-0) mercredi soir. Chelsea a mis du temps avant de faire craquer Paphos (1-0), tandis qu'une Juventus en manque de confiance s'est relancée face à Benfica (2-0)

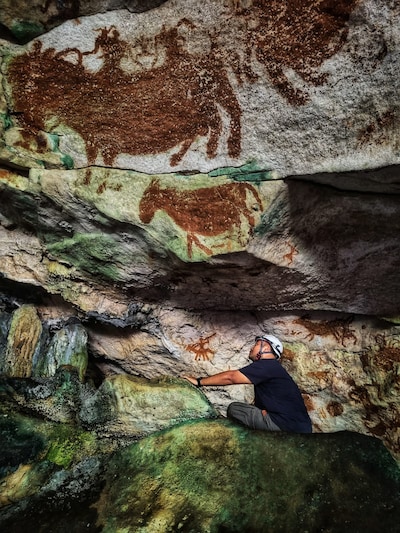

Grâce à Harry Kane, le Bayern Munich a assuré sa place dans le top 8 après sa victoire face l'Union Saint-Gilloise (2-0) mercredi soir. Chelsea a mis du temps avant de faire craquer Paphos (1-0), tandis qu'une Juventus en manque de confiance s'est relancée face à Benfica (2-0) La plus ancienne peinture pariétale au monde découverte en Indonésie

What is house burping? The winter trend explained

© Getty/iStock

Iran reports 3,117 protest deaths and issues new warning to US

There are fears the toll could increase significantly as information gradually emerges

© Middle East Images/AFP via Getty

Gavin Newsom says White House barred him from attending Davos event

Le sélectionneur du Maroc Walid Regragui élu entraîneur de la CAN 2025

Battu en finale de la CAN par le Sénégal, le Maroc a vu plusieurs de ses éléments être récompensés après la compétition. Walid Regragui, sélectionneur des Lions de l'Atlas, a été désigné meilleur entraîneur de la compétition.

Battu en finale de la CAN par le Sénégal, le Maroc a vu plusieurs de ses éléments être récompensés après la compétition. Walid Regragui, sélectionneur des Lions de l'Atlas, a été désigné meilleur entraîneur de la compétition. La plus ancienne peinture pariétale au monde découverte en Indonésie

Disney Lorcana’s Full Release Schedule for 2026 Confirmed

Disney Lorcana has seemingly gone from strength to strength since its debut, with Winterspell marking its eleventh set when it arrives in February.

Ravensburger has been pulling from just about everywhere in the Disney pantheon of heroes and villains, and this one will give us some Christmas-themed cards… a little too late for the event itself (but still cute, nonetheless).

Lorcana Release Schedule 2026 - At a Glance

- Winterspell - February 20 (Preorders Live)

- Wilds Unknown - May 15

- Attack of the Vines - Q3

- Coco and More - Q4

While Ravensburger has confirmed some new products coming this year, the second half of 2026 still remains something of a mystery. Here’s all we know coming to Disney Lorcana in the coming months, and we’ll update this as we hear more.

Winterspell - February 20

Winterspell, as we mentioned, has the unenviable task of offering cards related to Christmas almost two months late (or ten months early, if you’re an optimist). The set launches on February 20, with a prerelease on February 13, and will introduce snowy variants of characters.

Alongside the sweet snowy designs on the covers, if you're curious what comes with each of these items, here's the breakdown: the booster pack sets you up with 12 cards, including six Common cards, three Uncommon cards, two cards of either Rare, Super Rare, or Legendary rarity, and one random foil card. Preorders are now live, with Amazon being the best place to buy right now.

If you're hoping to have a bit more than just the booster pack on hand, the booster pack display comes with 24 packs. And for a little bit of everything, the Illumineer's Trove comes with a card storage box, six card dividers, eight booster packs, six damage-counter dice, and a lore counter.

Expect Mickey Mouse, Snowboard Ace, to bump shoulders with Jiminy Cricket, Willie the Giant, and Lonely Resting Place pulling double duty as the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future. Get ready for more card reveals in the coming weeks ahead of launch. TCGPlayer also has listings for individual cards, booster packs and boxes, and the new Illumineer’s Trove.

Scrooge McDuck Gift Box - March 13

While not tied to a fresh set, there are two new releases on March 13 which Collectors will want to be aware of. The first is the Scrooge McDuck Gift Box. It’s not up for preorder right now, but will include an exclusive Scrooge McDuck, S.H.U.S.H. Agent in Glimmer Foil, and five random booster packs.

The curious thing to note is that those packs are from prior sets, so you could get five from Winterspell, or you could end up with some classics. Up next, the Collection Starter Set has a portfolio adorned with Stitch, Rock Star, a Glimmer Foil variant of Stitch, Carefree Snowboarder, and four booster packs.

Wilds Unknown - May 15

With all due respect to Winterspell, this is the set that’s likely to take up a lot of the oxygen in Disney Lorcana’s 2026 release schedule. It’ll lean into cowboy fantasies, and who better to lead that charge than Woody himself, alongside Buzz Lightyear. Wild Unkowns marks a significant change for Lorcana releases, as the TCG leans more into Disney's Pixar characters, starting with The Incredibles and Toy Story.

This will also add new Prelease Kits to the Lorcana product pool, each including a promo card, dice, six booster packs from the latest set, and a deck box. Honestly, Ravensburger, you had me at Toy Story, but I’m excited to see the game grow.

I’ve also long lauded Gateway as a great starter product for new Lorcana players, but in May we’ll get also new 2-Player Starter Set with preconstructed decks, lore trackers, tokens, and some playmats, also as part of Wilds Unknown. This one launches on May 15, as recently confirmed, with prerelease from May 8.

Attack of the Vine - Q3

Looking further ahead, we don’t know a great deal about what’s coming later, but a few details have already been confirmed by the Lorcana team. Attack of the Vine, featuring characters from Monsters Inc and Turning Red, will launch sometime in Q3 2026.

Coco and More - Q4

Then, towards then end of the year, Coco is set to make its first Lorcana appearance, but we know little more than that. Disney’s possibilities are seemingly endless, though, and while Star Wars and Marvel each have cardboard appearances in Unlimited and Magic: The Gathering to prepare for, don’t be surprised to see the House of Mouse and Ravensburger pull out some even more deep cuts in 2026, and beyond.

Lloyd Coombes is an experienced freelancer in tech, gaming and fitness seen at Polygon, Eurogamer, Macworld, TechRadar and many more. He's a big fan of Magic: The Gathering and other collectible card games, much to his wife's dismay.

Lutnick’s speech slamming Europe at Davos leads to Lagarde’s abrupt exit: sources

La plainte visant Keylor Navas pour travail dissimulé classée sans suite

Un ancien employé de Keylor Navas avait déposé une plainte contre l'ex gardien du PSG, mais elle n'ira pas plus loin. Le parquet de Versailles a décidé de la classer dans suite, a appris l'AFP.

Un ancien employé de Keylor Navas avait déposé une plainte contre l'ex gardien du PSG, mais elle n'ira pas plus loin. Le parquet de Versailles a décidé de la classer dans suite, a appris l'AFP. Mercato : Andrés Gomez quitte le Stade Rennais et signe définitivement à Vasco de Gama

Recruté par Rennes en 2024, Andrés Gomez ne s'est pas éternisé en Bretagne. Le Colombien, prêté à Vasco de Gama depuis le début de saison, s'est engagé définitivement avec le club brésilien.

Recruté par Rennes en 2024, Andrés Gomez ne s'est pas éternisé en Bretagne. Le Colombien, prêté à Vasco de Gama depuis le début de saison, s'est engagé définitivement avec le club brésilien. House burping is the new winter trend - and it comes with health benefits

The trend can improve the air quality of your home

© Getty Images

Guinea-Bissau junta sets election date following last year's coup

© Copyright 2026 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Parachute Backup : cette app Mac ajoute une fonction indispensable à iCloud

Mercy Review

Mercy opens in IMAX and 3D theaters on January 23.

The screenlife genre gets a buggy update in Timur Bekmambetov’s Mercy, a rapid-action thriller in which a man accused of murder must prove his innocence to an AI judge within 90 minutes or be put to death. This clockwork setting has potential, but what it lacks, ironically, is execution. It’s often hilariously slapdash despite its conceptual prowess, and a prime example of great ideas being squished together and squandered…not to mention, made entirely headache-inducing if you watch it in 3D.

Right from the get-go, Mercy takes a strange approach to explaining its futuristic setting, beginning with a neatly edited “previously on” montage that lays out how the crime-ridden, poverty-stricken Los Angeles of 2029 came to adopt AI-driven capital punishment. Hilariously, it turns out this trailer for the film’s own premise is being shown to an accused killer, Detective Chris Raven (Chris Pratt), who ought to be more than familiar with the imposing AI entity Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson) since he pioneered the “Mercy” project that gives the film its name. Still, this exposition is somewhat forgivable, if only because it sets up the film’s parameters with the efficiency of LED screens lining the queue for a ride at Disneyland. Raven, who’s just regained consciousness in an enormous, empty room, is strapped to a lethal chair set to give off a fatal electrical pulse unless he can prove he didn’t murder his wife Nicole (Anabelle Wallis) earlier that day.

Before the restrained detective stands an enormous screen from which the imposing Maddox – her face silhouetted and cast in shadow – makes stern proclamations, deeming him “guilty until proven innocent,” and granting Mercy a not altogether uninteresting legal conundrum. Maddox also has unlimited access to the digital and GPS data of everyone in LA thanks to a communal cloud, which Raven can also sift through in order to prove his innocence. As either the judge or the accused bring up dueling evidence (courtesy of texts, doorbell videos, and countless other digital sources), iOS windows pop up in the space around Raven’s head like nifty 3D holograms. The case seems watertight: Raven arrived home during the work day, got into a fight with Nicole, and left, only for their teenage daughter Britt (Kylie Rogers) to find her stabbed minutes later.

The only problem is that Raven has no memory of the events depicted, an idea that seems intriguing until it’s quickly handwaved. From that point on, as the on-screen clock counts down, the story switches gears at breakneck speed and introduces a multitude of supporting characters via FaceTime calls, from Raven’s fiery police partner, Jacqueline “Jaq” Dialo (Kali Reis), to his diligent AA sponsor, Rob Nelson (Chris Sullivan), among many others. The mystery is unraveled practically backwards, with clues being explained or exposed in the very same moment they’re first discovered, while Raven uses Jaq as his proxy to revisit the crime scene and even chase down other suspects, viewing the world through her body cam, then a series of drones, then digital renderings of real spaces, then insert-new-idea-here without nearly enough time for us to adjust, let alone reflect. The movie switches focus just as haphazardly, going from tech conspiracy to domestic drama to some errant mixture of drugs-and-terrorism thriller that becomes impossible to invest in given the sheer flurry of images and pop-up windows flying at you at once. These are also never in the same plane of focus, forcing your eyes to adjust faster than you can process information, which becomes even more physically demanding in 3D.

However, what is perhaps strangest about Mercy is what it has to say – and often, what it doesn’t say – about technology. Its setting involves an omniscient state apparatus that uses bare-bones facts to make snap judgements before sending people to their deaths. And yet, this instant access to all facets of people’s lives doesn’t end up remotely framed as a dilemma or inspire any hesitation (the way it does in, say, the climax of The Dark Knight). The neutral approach to all-encompassing surveillance isn’t a bad thing in and of itself – after all, it’s the foundation of Mercy’s mystery setting – but paired with the film’s eventual pro-AI bent, despite depicting AI as a fascistic entity, it’s hard not to be perturbed by what Bekmambetov is selling.

Screenlife has been one of the more interesting filmic byproducts of the internet age, dating back to webcam experiments like the French comedy, Thomas in Love (2000), and the American supernatural horror film, The Collingswood Story (2002), and culminating in perhaps the ultimate example of the concept just last year: the reviled Ice Cube vehicle, War of the Worlds. Bekmambetov has produced a number of screenlife films: the Unfriended series; the father-daughter mystery, Searching (2018); and the modern Shakespeare adaptation, R#J (2021). He knows better than anyone that the challenge of screenlife is the self-imposed limitations of telling a story as it plays out within the confines of a computer screen.

But with Mercy, Bekmambetov pushes the concept past its limits until it breaks and becomes uninteresting in the process. Sure, we see digital evidence through Raven’s eyes, but half the time, the camera is focused on Pratt’s aggressive close-ups as the story reveals his character to be an unpleasant, borderline irredeemable husband and policeman whose innocence becomes hard to root for. Ferguson’s shadowy AI magistrate, by comparison, comes off as far more human…which is an incredibly strange outcome. There’s no emotional challenge or cognitive dissonance in wanting Raven to break free – the film’s approach to morality is dispiritingly flat – and Pratt often fails to imbue the character with realistic emotions or even the kind of showiness that might make Mercy an operatic romp. If nothing else, watching Pratt struggle with the material is at least a reminder of the flawed human artistry on display.

When the story eventually departs from its courtroom confines in its final act, the question of whose perspective – or cameras – we’re seeing the world through, and why, is just as nagging as the movie’s tonal inconsistencies and sloppy action scenes that cut between too many visual sources. The promise of unfurling a screenlife story into three-dimensional space around a character forced to interact with it is an alluring concept, especially when it concerns the wealth of information at Maddox’s and Raven’s fingertips. And yet, Bekmambetov never goes beyond simply introducing these ideas, casting them into the ether without a second thought. In a world that’s as radically changed as the one we see here, and as theoretically dangerous, you need a story that engages with its own premise on at least some level, and allows its doomed protagonist to wrestle with notions of morality and his own culpability in creating this status quo. Mercy is not only not that movie, but it also seems to salivate at the thought of a world where punitive justice and invasions of privacy are possible and easy, and the only downside is rogue actors who might misuse these technologies, which is a conclusion the film practically narrates to the camera.

Perhaps the screenlife genre, or this particular rapid version of it, isn’t the right venue for the material to begin with. On one hand, the images represent a kind of voyeuristic invasion and a ceding of liberty, which might have been interesting to explore. On the other hand, the sheer flurry of these invasive pop-up windows is also how the movie conjures its few moments of intrigue and excitement. Watching Mercy, it’s hard not to wonder: Why even make a futuristic sci-fi movie set in a dystopia if your fawning aesthetic framing makes the setting feel utopic? At that point, Bekmambetov may as well just invest in a generative AI company instead; oh, wait...

Parachute Backup : cette app Mac ajoute une fonction indispensable à iCloud

Michelle Obama warns America is still not ready to elect a woman president

C’est la fin des smartphones ASUS et nous sommes sûrs que vous savez pourquoi

Le président Jonney Shih fait une annonce tonitruante. Asus ne produira plus de nouveaux smartphones pour prioriser un autre secteur en pleine expansion.

C’est la fin des smartphones ASUS et nous sommes sûrs que vous savez pourquoi

Le président Jonney Shih fait une annonce tonitruante. Asus ne produira plus de nouveaux smartphones pour prioriser un autre secteur en pleine expansion.